The little-known virus that surged in children this year - BBC News

In early 2021 staff at Maimonides Children's Hospital in Brooklyn, New York, were starting to feel a cautious sense of relief. Covid-19 cases in the city were falling. As a side effect of social distancing, mask-wearing and hand-washing, they had also seen far fewer other viral infections, such as the flu. But then in March a growing number of coughing children and babies arrived at the hospital, some of them struggling to breathe.

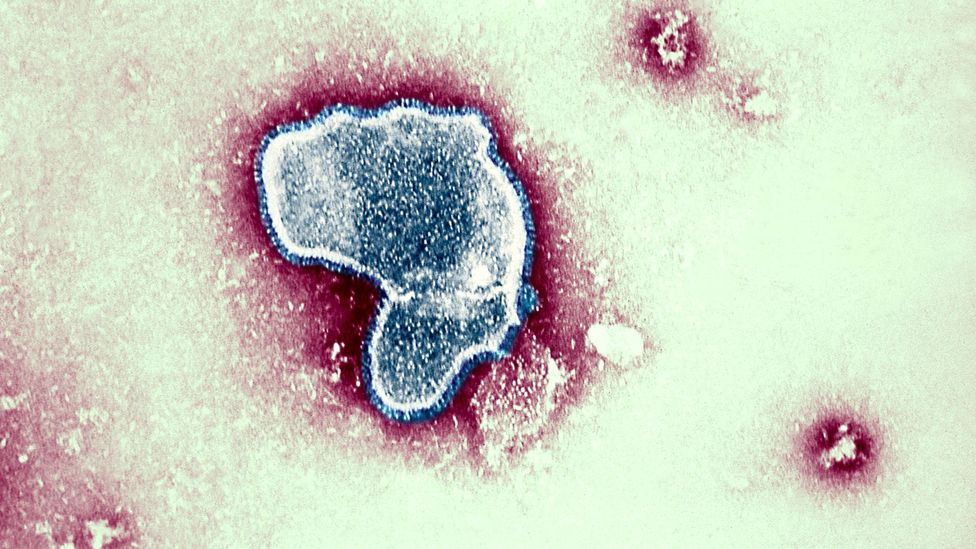

They'd been infected with RSV, short for respiratory syncytial virus, a common winter bug that can cause lung problems. At this time of the year, RSV cases should have been dwindling. Instead, they were soaring.

Over the months that followed, out-of-season RSV surges would disrupt summers in places as far afield as the southern US, Switzerland, Japan and the UK. The virus's strange behaviour appears to be an indirect consequence of the Covid-19 pandemic, doctors say. Last year, lockdowns and hygiene measures suppressed the spread of coronavirus, but also other viruses such as RSV. As a result, children did not have the opportunity to build up immunity against them.

Once the measures were loosened, RSV found a large pool of susceptible babies and children to infect, leading to sudden surges at unexpected times. A previously fairly predictable bug turned into one that could surprise hospitals and families at any time of the year. The unseasonal outbreaks stretched wards to their limits, put families on alert, and showed just how deeply Covid-19 and the associated measures had reshaped the world.

For staff on the ground, the experience was dramatic.

The respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) is a common single-RNA stranded virus that causes infected cells to fuse together (Credit: BSIP/UIG/Getty Images)

"Our ICU (intensive care unit) again became overwhelmed, this time not with Covid, but with another virus," recalls Rabia Agha, the director of the division of paediatric infectious diseases at Maimonides Children's Hospital. At the peak of the outbreak, in early April, the majority of children admitted into the ICU were being admitted for RSV.

Around the world, the virus ripped through populations of young children who had been shielded from infectious diseases for months, and were now suddenly exposed to them.

"It surprised us. We knew that it was something to look out for, but we didn't think it would be that many," says Christoph Berger, head of the department of infectious diseases and hospital epidemiology at the University Children's Hospital in Zurich.

At his hospital, RSV cases usually peak in January, and hover around zero in the summer months of June to August. This year, there were no cases in winter. Instead, they began to rise steeply in June, then soared to 183 infections in July, higher than in previous winter seasons.

"We were full, every single bed was occupied, and that's a challenge," Berger recalls of the height of the outbreak in July. His hospital had to transfer sick babies and children with RSV to other hospitals that still had space. Several other Swiss hospitals experienced the same.

RSV posed a bigger problem for them than the coronavirus during the summer in Switzerland. "We had almost no Covid cases during that period," says Berger. The few children who came to the hospital with Covid recovered relatively quickly. "Those with RSV stayed longer," he says.

An RSV infection is not in itself a cause for alarm. According to the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, most children will have had one by the time they are two years old. The majority will experience it as a cold-like illness, with a runny nose and cough, and recover by themselves. But in some babies and young children, it can cause bronchiolitis, an inflammation of the lower parts of the lung. They may struggle to breathe and feed.

About 1-2% of babies under 6 months old with RSV have to be taken to hospital and given extra oxygen through a mask or tubes in their nose to help them recover. Some may also require a feeding tube. With that support, most will get better within a few days.

Before the coronavirus pandemic, hospitals routinely prepared for RSV surges ahead of winter. The most at-risk patients, such as premature babies and those with existing lung and heart problems, can be protected with palivizumab, a shot of antibodies that helps fight off the virus. The shot needs to be given every month throughout the months when RSV is active, another reason why preparing for surges is so crucial.

Children that get sickest with RSV can often be treated with oxygen and most get better in a few days (Credit: Getty Images)

The pandemic has disrupted that seasonal rhythm, and its role in the usual development of children's immunity.

"With the measures we had for Covid, people were not meeting, people were not travelling, and people were being very careful with masking and distancing," says Agha. "And that truly helped to keep Covid as well as all other viruses at bay. So, one season of this RSV was completely missed. And if you skip one season, then you are not producing antibodies against it, and mothers are not producing antibodies that can then be passed on to babies."

As a result, those babies may then be particularly vulnerable to RSV when the world re-opens. Data from different countries supports that idea of an immunity gap due to a skipped season. "The greatest relative increase in cases are in children aged one, who 'missed' an RSV season last autumn/winter", officials at Public Health England said in an email to the BBC, describing the surges seen in parts of England over the summer there.

You might also be interested in:

- What long Covid is revealing about disease

- How Covid-19 is changing the world's children

- Is the Western way of raising kids weird?

A skipped season increases the pool of susceptible babies and children, since it includes those who were shielded during the winter, as well as those born since then. That may make viral surges more powerful when they eventually hit. In Tokyo, researchers have reported the largest annual rise in RSV cases since monitoring began in 2003. They suggest the build-up of susceptible people during the pandemic may have contributed to the unusually big outbreak this year.

Other aspects of the new viral landscape are still unclear, such as the question of why RSV surged once anti-Covid measures were loosened, but not the flu, which has remained fairly subdued. The precise pattern of the out-of-season RSV surges has also varied somewhat from country to country. Agha and her team in Brooklyn observed that their surge was unusually severe, affecting much younger children than usual and sending a higher proportion into intensive care. But in Australia, for example, it affected an older age group than before. Berger says that the Swiss summer outbreaks had been no more severe than typical winter surges.

Children with health problems that put them most at risk of RSV can be given a protective shot of antibodies (Credit: Jeff Gritchen/Orange County Register/Getty Images)

One big question is what this new pattern means for the coming months. A summer surge does not necessarily mean there won't be more cases when the weather turns cold. And in some areas, cases are only beginning to rise now, in early autumn.

"RSV, and the bronchiolitis that it causes, is definitely the key thing that at the moment the children's hospitals are planning for, expecting, beginning to see and looking after," says Sophia Varadkar, deputy medical director and consultant paediatric neurologist at Great Ormond Street Hospital for Children in London.

At her hospital, cases have started rising, and she expects to see more in the coming weeks. For those caring for babies, RSV can be a greater worry than Covid-19, says Varadkar. "Covid for children, in general, was not a significant illness. It did not make many children really unwell. RSV is a potentially bigger illness, [affecting] many more children, and we definitely know that it can make those small babies unwell," she says.

With schools reopening, viruses including RSV will have more opportunities to spread. But adults' behaviour may be even more crucial. In Switzerland, nurseries and playgroups remained open throughout the winter, and young children did not wear masks. Yet almost no children came down with viral infections such as RSV and the flu that winter, presumably because the adults' hygiene measures helped protect them.

"People always say that the children infect the adults, but if you think about it, that wasn't the case at all here, it was the other way round," says Berger. "When adults and older children wear masks, observe social distancing and wash their hands, we see neither flu nor RSV. And when they loosen their measures, the virus circulates again, and more young children end up in hospital."

Even after the summer surge, his hospital remains on guard. "I have no idea how this will continue, and whether those were all the cases, or whether we'll see another wave in winter – I don't know."

Hand-washing, and keeping vulnerable babies away from people with runny noses and coughs, can help the spread of infection. It can also flatten the peak of an RSV epidemic, ensuring hospitals have the capacity to look after every child who needs help.

"For most of the children, it will be a mild illness, they can be looked after by their parents, they just need comfort, more frequent feeds, a quiet time, some paracetamol if they have a temperature, and that's all that they need," says Varadkar in London. But if the baby is struggling to breathe or feed, or parents feel something is just not right, they should seek help, she says.

At Maimonides Children's Hospital in Brooklyn, the peak of the RSV surge has passed. But Agha sees a broader lesson for hospitals adjusting to a post-Covid-19 world.

"What it taught us was that you have to be prepared," says Agha. "These are not the same times as two years ago. Life has changed, the world has changed, and these viruses are evolving and behaving in unexpected ways."

--

Join one million Future fans by liking us on Facebook, or follow us on Twitter or Instagram.

If you liked this story, sign up for the weekly bbc.com features newsletter, called "The Essential List". A handpicked selection of stories from BBC Future, Culture, Worklife, Travel and Reel delivered to your inbox every Friday.

Comments

Post a Comment