Those who recall early days of polio vaccine weigh in on COVID-19 - The Columbian

Those who recall early days of polio vaccine weigh in on COVID-19 - The Columbian |

| Those who recall early days of polio vaccine weigh in on COVID-19 - The Columbian Posted: 15 Jun 2021 06:04 AM PDT  CINCINNATI — The COVID-19 pandemic and the distribution of the vaccines that will prevent it have surfaced haunting memories for Americans who lived through an earlier time when the country was swept by a virus that, for so long, appeared to have no cure or way to prevent it. They were children then. They had friends or classmates who became wheelchair-bound or dragged legs with braces. Some went to hospitals to use iron lungs they needed to breathe. Some never came home. Now they are older adults. Again, they find themselves in what has been one of the hardest-hit age groups, just as they were as children in the polio era. They are sharing their memories with today's younger people as a lesson of hope for the emergence from COVID-19. Clyde Wigness, a retired University of Vermont professor active in a mentoring program, recently told 13-year-old Ferris Giroux about the history of polio during their weekly Zoom call. Families and schools saved coins to contribute to the "March of Dimes" to fund anti-polio efforts, he recalled, and the nation celebrated successful vaccine tests. "As soon as the vaccine came out, everybody jumped on it and got it right away," recounts Wigness, 84, a native of Harlan, Iowa. "Everybody got on the bandwagon, and basically it was eradicated in the United States." In the late 1940s and early 1950s, before vaccines were available, polio outbreaks caused more than 15,000 cases of paralysis each year, with U.S. deaths peaking at 3,145 in 1952. Outbreaks led to quarantines and travel restrictions. Soon after vaccines became widely available, American cases and death tolls plummeted to hundreds a year, then dozens in the 1960s. In 1979, polio was eradicated in the United States. "So really, what I would love for people to be reassured about is that there have been lots of times in history when things haven't gone the way we've expected them to," says Joaniko Kohchi, director of Adelphi University's Institute for Parenting. "We adapt, and our children will have skills and strengths and resiliencies that we didn't have." While today's children learned to stay at home and attend school remotely, wear masks when they went anywhere and frequently use hand sanitizer, many of their grandparents remember childhood summers dominated by concern about the airborne virus, which was also spread through feces. Some parents banned their kids from public swimming pools and neighborhood playgrounds and avoided large gatherings. "Polio was something my parents were very scared of," says Ohio Gov. Mike DeWine, now 74. "My dad was a big baseball fan, but very careful not to take me into big crowds … my Dad's friend thought his son caught it at a Cardinals game." A 1955 newspaper photo surfaced recently showing DeWine becoming one of the first second-graders in Yellow Springs, Ohio, to get a vaccination shot. His future wife, Fran Struewing, was a classmate who got hers that day, too. Sixty-six years later, they got the COVID-19 vaccination shots together. DeWine, a Republican, has drawn criticism within the state and his own party for his aggressive response to the COVID-19 outbreak. But he and Senate Minority Leader Mitch McConnell, a Kentucky Republican who overcame a childhood case of polio, and others of that time remember the importance of developing vaccines and of widespread inoculations. Martha Wilson, now 88 and a student nurse at Indiana University in the early 1950s, remembers the nationwide relief when a polio vaccine was developed after years of work. She thinks some people today don't appreciate "how rapidly they got a vaccine for COVID." She doesn't take for granted returning to the kind of safer life that allows for planning a big family reunion around Labor Day. Kohchi had a different experience than most children of the 1950s. Her mother, a believer in natural medicine such as herbal treatments, didn't have her vaccinated (Kohchi got vaccinated as an adult). While her mother was an outlier then, she would fit in with today's vaccine skeptics. DeWine thinks a key contrast between the 1960s and today, with its reluctance of so many Americans to get vaccinated, is that polio tended to afflict children and had become many parents' worst nightmare. "I know our parents were relieved when we were finally going to get a shot," Fran DeWine recalls. Her husband recently initiated a series of $1 million lotteries to pump up sluggish COVID-19 vaccination participation among Ohioans. President Joe Biden last week announced a "month of action" with incentives such as free beer and sports tickets to drive U.S. vaccinations. Wigness blames today's divisive politics and anti-science messages spread over talk shows and social media. Ferris, the teen he mentors, says he sees criticism of mask-wearing and other precautions among some of his peers. Ferris says the polio eradication success "certainly means it's possible we can beat COVID, but it entirely depends on people." Martha Wilson, now living in Hot Springs Village, Ark., talked about polio and COVID-19 in a recent Zoom call with her granddaughter, Hanna Wilson, 28, of suburban New York. She reflected on treating patients iron lungs, a kind of ventilator used to treat polio. "They were very confining. … It was not a very nice life," says Wilson. "I remember a book I read when I was a little kid, 'Small Steps: The Year I Got Polio,' by Peg Kehret. And it stuck with me," Hanna says. "And I remember the iron lungs and things like that. But when I asked people about it — 'Hey, do you remember what polio was?' — no one knew." Hanna, an athletics administrator for the Big East Conference, happened to be in Iran in December 2019 when she heard the first reports of a new virus in China. She was visiting a grandfather, Aboulfath Rohani, who would die there a few months later at age 97. Back home, her job was quickly transformed. Games, then tournaments, then entire seasons were canceled. "It's been eye-opening,' she says. "So many people denied that it was real, they hadn't seen anything like this." Both she and her grandmother point out that the nation endured not only polio but a deadly flu pandemic in 1918 whose estimated toll remains higher than COVID-19's both in the United States and globally. "I'm hopeful we will come out of this and it will be just another chapter in history," Hanna Wilson says. Martha Wilson says her mother-in-law survived illness from the 1918 flu pandemic and lived a long life. "So that was one generation, polio was another generation, COVID's another," she says. "I think they happened so far apart that we'd forgotten that these things do happen. I think COVID caught us by surprise. "And now Hanna and her generation will be maybe more aware when something else comes along." |

| Fact check | History shows India did not lack access to vaccines as claimed by PM Modi - The Hindu Posted: 07 Jun 2021 09:05 PM PDT

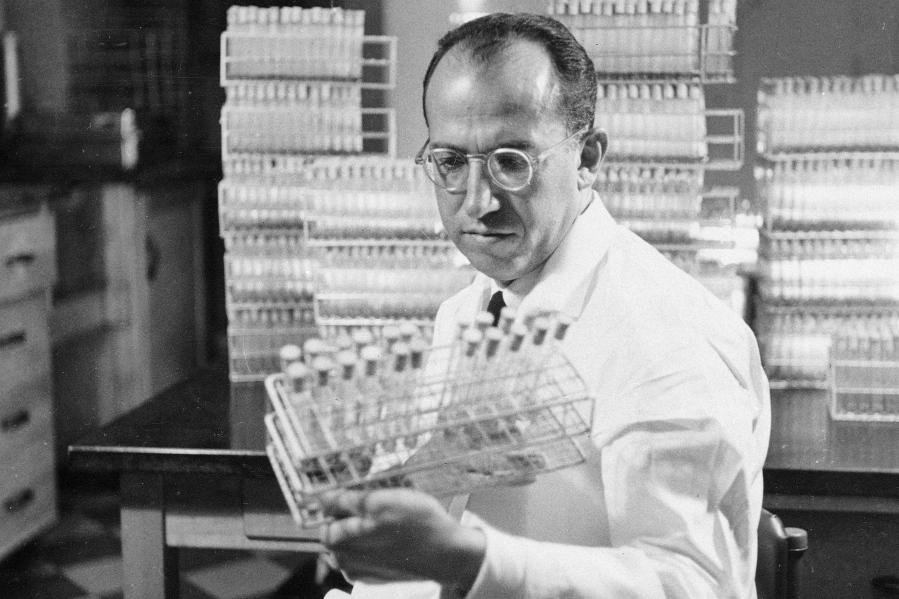

India, even before Independence, was among the countries that indigenously manufactured vaccines almost years within they were discovered, historical records suggest.Prime Minister Narendra Modi's speech on Monday presented a view of India's vaccination history that is at odds with the facts. "If you look at the history of vaccinations in India, whether it was a vaccine for smallpox, hepatitis B or polio, you will see that India would have to wait decades for procuring vaccines from abroad. When vaccination programmes ended in other countries, it wouldn't have even begun in our country," claimed Mr. Modi in his address. India, even before Independence, was among the countries that indigenously manufactured vaccines almost years within they were discovered, historical records suggest. While there have been several challenges to the uptake of vaccines, their availability was the least of the problems. Smallpox vaccineA vaccine for smallpox, as a history of vaccination in India published in the Indian Journal of Medical Research (IJMR), by Dr. Chandrakant Lahariya, in 2012, says was first administered to a three-year-old Indian, in 1802, a mere four years after English physician Edward Jenner published result of his experiments on inoculating subjects with a cowpox virus. The smallpox vaccines were imported into India until 1850 but preserving the liquid lymph solution was a challenge. This led to institutes in India researching ways to increase lymph supply with early success by 1895. Also read: U.S. vaccine 'gift' to India may not be substantial The first animal vaccine depot was set up in Shillong in 1890 from where it started to be produced. While vaccination never ceased in India once it began, it had varying popularity. There was hesitancy, opposition from 'tikadaars' (who performed variolation) and those actually administering vaccines charged a small fee contributing to its fluctuating uptake. "The vaccination coverage went down and in 1944-1945 in India, the highest numbers of smallpox cases in the last two decades were reported. As soon as the World War II ended, the focus was brought back on smallpox vaccination and cases decreased," says Dr. Lahariya, "In 1947, India was self-sufficient in the production of smallpox vaccines." The years also saw changes in the smallpox vaccines, experiments on the appropriate dosage, monitoring of adverse events. Smallpox was eliminated in North America and Europe by 1953. In 1959, the World Health Organization (WHO) started a plan to rid the world of smallpox. This was again a challenging programme that saw variable success and only a Intensified Eradication Programme in 1967, according to a historical note on the website of the U.S. Centres for Disease Control. It took until 1971 to eradicate the virus in South America and 1975 in Asia (and India) and 1977 in Africa. The challenge, said Dr. Lahariya, was not lack of access to vaccine but social and economic factors surrounding vaccination. Pioneer in polio researchThe history of polio vaccination in India is more complicated. "India was also the pioneer-leader in polio research — epidemiology, vaccine-prevention — and in the manufacture of both Oral Polio Vaccine (OPV) and Injectible Polio Vaccine (IPV). India's lead position was squandered in later years due to short-sighted policies and capricious decisions, a blot in our history of public health," write T. Jacob John and M. Vipin Vashishta in 2013 edition of the IJMR. The inactivated polio vaccine, that was developed in the U.S. by Jonas Salk and successfully used for polio eradication campaigns, was also adopted in some European countries. The OPV was developed by 1960 and over the years proved itself a better vaccine because it could be given sans an injection, worked quickly and conferred longer immunity. The Pasteur Institute of India developed and produced, for the first time in India, an indigenous trivalent OPV in 1970. Manufacture of the IPV was discouraged in India primarily because there were worries that the seed virus, necessary for manufacture, could escape out of the lab. It was not until 2006 that IPV was licensed for manufacture in India. Over the years, it was observed that the OPV had lowered efficacy, was linked with not only seeding new vaccine derived polioviruses (VDPVs) but also caused vaccine-associated paralytic polio (VAPP). It was through the use of a combination of both kinds of vaccines, concerted sustained campaigns, huge historical endemic presence of the virus, the populations at risk and inadequate attention by governments to boost vaccine production that it required until 2011 to eliminate polio. Again, it was not because India was unable to make those vaccines. Mission IndradhanushThe Prime Minister also claimed that since 2014, the Mission Indradhanush programme had increased the percentage of children covered under vaccination from 60% to 90%. The latest round of the National Family Health Survey, that only provides data from 17 States and five Union Territories, showed that none of the States had achieved 90% vaccination coverage. The Health Ministry had released data on this on December 2020 and was expected to provide data from remaining States by May this year. Only five States: Himachal Pradesh, West Bengal, Karnataka, Goa and Sikkim exceeded coverage by 80% with Himachal Pradesh touching 89%. Mission Indradhanush targets one dose of BCG vaccine, which protects against tuberculosis; three doses of DPT vaccine, which protects against diphtheria, pertussis or whooping cough and tetanus; three doses of the polio vaccine; and one dose of the measles vaccine. A vaccine for against the bacterium causing plague was made by Waldemar Haffkine at the Grant Medical College, Bombay, in 1897 that he first tested on himself and later on, on the inmates of Byculla jail. A Plague Laboratory was set up in 1899 and in 1925 renamed the Haffkine Institute. Several vaccine institutes came up in different provinces of the country, including the 1948 BCG (for tuberculosis) Laboratory in Guindy, Madras. These institutes enabled the manufacture of vaccine for diptheria, pertussis and tetanus in India, before 1940. Several public sector vaccine units that produced much of India's vaccines were, at various instances, shut down, or their capabilities diminished, giving way to private companies such as the Serum Institute of India and Bharat Biotech to become the vaccine manufacturing power houses and global suppliers. |

| You are subscribed to email updates from "polio history" - Google News. To stop receiving these emails, you may unsubscribe now. | Email delivery powered by Google |

| Google, 1600 Amphitheatre Parkway, Mountain View, CA 94043, United States | |

Comments

Post a Comment