In India’s eradication of smallpox and polio, lessons on how to (and how not to) tackle Covid-19 vaccination - The Indian Express

In India’s eradication of smallpox and polio, lessons on how to (and how not to) tackle Covid-19 vaccination - The Indian Express |

| Posted: 12 May 2021 12:00 AM PDT On June 14, 1802, Anna Dusthall, a three-year-old girl of a mixed racial parentage in Bombay, was given a dose of cowpox vaccine that the Scottish doctor Helenus Scott had received from Basra in the Middle East. Scott had injected the vaccine in about a dozen or so children, and Dusthall was the only one who took the infection. A little over a week later, he observed a vaccine vesicle on her arm, the lymph from which was used to inoculate other children, five of them being in Bombay. Very little is known about Dusthall, except that her "quietness and patience in suffering the operation" had ushered a new epoch in the history of medicine in the subcontinent. Less than a month later, on July 2, Scott wrote to the Bombay Courier to announce, "we have it now in our power to communicate the benefit of this important discovery to every part of India, perhaps to China and the whole eastern world." Dusthall's inoculation was indeed the beginning of the end of one of the deadliest diseases that afflicted modern humankind. A highly contagious viral infirmity, the smallpox killed upto half of those it infected, severely maiming others through scarring of the skin, blindness and even infertility. It is only about one and a half centuries later from the first case of vaccination that India and the planet would be declared free of the disease. Soon after, the country decided to launch the National Immunisation Programme in 1978 (later renamed as Universal Immunisation Programme in 1985) with the introduction of BCG vaccine for Tuberculosis, the Oral Polio Vaccine, the Diphtheria, Pertussis (Whooping cough) and Tetanus (DPT) vaccine and the vaccine against typhoid-paratyphoid. By the mid-1980s, a multinational public health effort began to eradicate Polio, a disease caused by the poliovirus which can affect the central nervous system leading to flaccid paralysis. "The ongoing vaccination drive for Covid19 is the first large scale programme for the adult population. Also the sheer number of people to be vaccinated is far higher than previous ones," explains Dr Chandrakant Lahariya, public policy and health systems expert who has recently authored the book, 'Till we win: India's fight against Covid-19 pandemic.' Lahariya says that even though the smallpox vaccine was administered among adults, the approach of the drive was very different and largely restricted to identified areas like Madhya Pradesh, Uttar Pradesh and Bihar where the disease was more prevalent. Neither was it a countrywide vaccination programme, nor was it done all-year round.

It is equally important to remember how the political and social landscape of the country has evolved since the 19th century, which certainly impacted the way vaccines were administered and perceived. Nonetheless, both the smallpox and polio vaccine campaigns provide important insights into the challenges, failures and achievements of large-scale immunisation programmes in the country. The early beginnings of the smallpox vaccineThe smallpox vaccine arrived in India at a time of British colonial expansion. "From the outset, the introduction of vaccination was associated with war and imperial expansion. Beginning in Bombay in June 1802, it was firmly established in British India and in the new colony of Ceylon during 1803, and more than a million Indians and Sri Lankans had been vaccinated by 1807," writes historian Michael Bennett in his book, 'War against Smallpox: Edward Jenner and the global spread of vaccination.' Thereby, a lot of politics, power and persuasion was used by EIC officials to introduce the vaccine in India. The vaccination was conducted by 'trained vaccinators' also called tikaadars, who were mostly Indians and would travel from one place to another. The Tikadaars were a product of the existing system of immunisation in India, called variolation, whereby the vaccinator would induce the smallpox vaccine with preserved dried scabs from previously inoculated subjects. In the 19th century, the practise came to be thoroughly criticised, and equated with practices like the Sati and female infanticide. Bennett writes that the British authorities in India had many reasons to be interested in vaccinating Indians. To begin with, the maintenance of vaccine supply depended on vaccinating a larger number of children than were available to the expatriate community. Indian children were systematically used for the purpose. For instance, two children were sent from Bombay to Tellicherry down South, where the surgeon used the lymph from their arms to inoculate 23 children, some of whom were then taken to further vaccinate others along the Malabar coast. The use of children was not completely consensual, although there are references to mothers being paid to travel with their children for the purpose of vaccination.

The path to vaccination was not an easy one, given the hesitation from Indian subjects, particularly on account of cultural and religious factors. The upper caste Hindus were particularly ill disposed towards the vaccine coming from the cow. Then there was the belief that the goddess of smallpox would be angered by vaccination. Interestingly, a notable voice of vaccine hesitation, though much later, was that of Mahatma Gandhi. Historian Niels Brimmes in his article, 'Fallacy, sacrilege, betrayal and conspiracy: the cultural construction of opposition to immunisation in India', notes that vaccination violated Gandhi's religious instincts, his vegetarianism and his notion of purity. In an article penned down by Gandhi in 1913, he expressed his abhorrence towards vaccines: "Vaccine from an infected cow is introduced into our bodies; more, even vaccine from an infected human being is used… I personally feel that in taking this vaccine we are guilty of a sacrilege." By the second half of the 19th century, significant research and investment was being made for the production and preservation of vaccine supply in India, as transport from Great Britain was proving to be rather challenging. Further, in 1898, the arm-to-arm method of vaccination was banned, citing the spread of syphilis and hepatitis through the practise. Calf lymph was the preferred method now, and was also more acceptable, given that it did away with issues of caste and religion which was cause for concern in case of lymph being transferred from one person to another. By the dawn of the 20th century, the immunisation campaign was met with a number of political challenges. First among these was the Government of India Act of 1919, which devolved a number of administrative powers from the centre to the provinces. Thereby, self-governments were given the responsibility of providing vaccination. "'The 1919 Act originated with good intentions but the local government had limited financial capacities to fund vaccinators and often led to the variable efforts and progress on smallpox vaccination," writes Lahariya in his article, 'A brief history of vaccines and vaccination in India'. Moreover, with the beginning of the Second World War in 1939, vaccination efforts went down further. Lahariya writes that in the period between 1944-45, the largest number of smallpox cases were reported for the last two decades. By the time of the Independence of the country, India was reporting the highest number of smallpox cases in the world. The vaccination efforts by the British in India need to be understood in context of the political benefits that colonisation derived from it. "Vaccination was an activity that the British rulers would flag up in order to counter any criticism of the extractive nature of imperial rule in India," says Sanjoy Bhattacharya, Professor in history of medicine at the University of York. The campaign gave the impression of the British being benevolent rulers. In princely states like Mysore and Hyderabad, vaccination emerged as a source of soft power. Bennett notes that after the conquest of Delhi, Mughal Emperor Shah Alam expressed an anxious desire to have his grandchildren vaccinated as smallpox was raging in the city. "In June 1805, the son and daughter of Akbar Shah, the emperor's eldest son, were vaccinated and lymph from their arms was used to safeguard four more of the house of Timur," he writes. He further writes that one big advantage the British had on the banks of the Sutlej river in 1809 was the introduction of the vaccine in Punjab, where the Sikhs gladly accepted it. The effort to eradicate smallpox in Independent IndiaBhattacharya says that after Independence, Nehru and the first health minister, Rajkumari Amrit Kaur, realised that if they did not keep up with the vaccination service for smallpox, they would be criticised for being a regime much worse than the British rule. Therefore investment in smallpox vaccine production and vaccination continued at a very impressive scale. "Both Nehru and Kaur also realised that good smallpox vaccine production capability gave India a lot of soft power in terms of foreign policy. At least in South Asia, India was a major supplier of smallpox vaccine whenever a pandemic broke out in countries like Nepal, Burma," he says. From the early 1950s, global health experts began discussions around the possible eradication of smallpox. In 1958, after much deliberation the World Health Assembly (WHA) passed a resolution to eradicate the disease, an announcement which had massive implications on the health infrastructure of India. India started the National Smallpox Eradication Programme (NSEP) in 1962, with the target of vaccination the entire population in the next three years. "However, after five years of implementation, the coverage remained low and outbreaks were still being reported. This was because the difficult to access population was not being reached and many a times the same individuals were being vaccinated for inflating coverage," writes Lahariya. From 1964 onwards the vaccination strategy was reformulated. The focus was now on Bihar, Uttar Pradesh, Madhya Pradesh and West Bengal where smallpox was most prevalent. The introduction of the bifurcated needle technique and the availability of a more potent, heat stable and freeze dried vaccine in place of the liquid vaccine simplified the process and increased vaccine uptake.

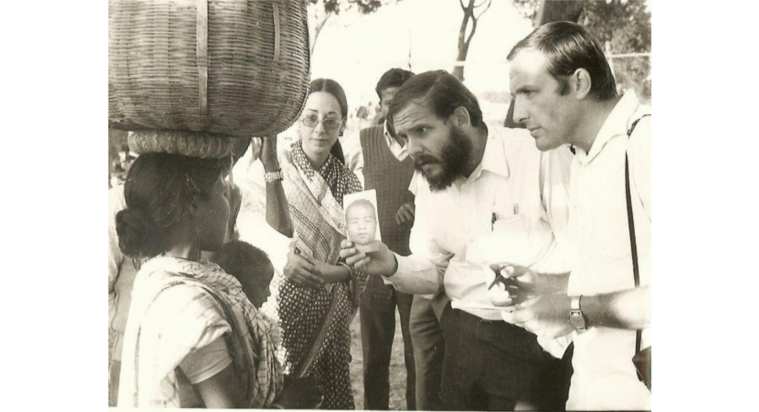

Beginning from 1973, an intensified eradication campaign was launched under the general guidance of the WHO. The key feature of the programme was active surveillance- aggressively seeking out cases rather than waiting for them to be reported. "Surveillance teams were equipped with jeeps and motorcycles so that they could roam near and far searching markets, schools, pilgrimage sites, tea shops and bastis for cases," writes historian Paul Greenough in his article, 'Intimidation, coercion and resistance in the final stages of the South Asian smallpox eradication campaign, 1973-1975'. When active cases were located, the patients were either confined to their homes with guards or put in hospitals. Local vaccinators were then hired to immunise co-villagers regardless of their prior immune status. A most striking feature of the eradication campaign was the aggressive use of coercion. Greenough writes in great detail about the military operations where villages were surrounded and a mix of international and Indian workers would go and kick people's doors, go and sit on top of people and forcibly vaccinate them. One of the many such incidents he narrates is that of a particularly violent encounter in a village in Bihar in 1975, as narrated by Lawrence Brilliant, a WHO physician-epidemiologist. As per his account, a government intruder broke through the door of a hut in the middle of the night. The inhabitant, Lakshmi Singh woke up screaming and hid herself. Her husband, Mohan Singh chased out the official with an axe in his hand, but was quickly overpowered by a team of doctors and policemen. He was pinned to the ground while a vaccinator jabbed the vaccine in his arm.

Bhattacharya explains that the memory of this use of force is still fresh since the history of the eradication of smallpox is fairly recent. It was only in the late 1970s that smallpox was declared eradicated in India. "Those bodies that were sat on so unceremoniously are now grandparents or parents. These memories have not disappeared. It won't be surprising that any effort at forcible Covid vaccination in Eastern Uttar Pradesh or Bihar where this sort of force was the highest, will be resisted," he says. On a positive note, however, the smallpox eradication campaign did carry some important lessons. Smallpox was eradicated through the arm power of hundreds and thousands of community workers both men and women. "Female community workers were central to the control of smallpox. There were thousands of women who went into houses and spoke to mothers and grandmothers, convincing them to vaccinate their children," says Bhattacharya. "Smallpox was eradicated not just because of an effective vaccine, but because of a strong workforce. The hand that holds the vaccine is as important as the vaccine," he adds, suggesting that strengthening of community healthcare is the key requirement in the current vaccination drive against Covid 19. The door-to-door campaign to eradicate PolioThe eradication of smallpox was a big success story in that it shaped up the structure of immunisation efforts in the country for the future. "The eradication of smallpox paved the way for the development of an infrastructure for the universal immunisation programme," says Lahariya. In 1988, the World Health Assembly passed a resolution for polio eradication by 2000. Before that, there were state-specific efforts to immunise people against polio. Tamil Nadu, for instance, had conducted the 'Polio Plus' programme in 1985. In 1994, an expanded project to eradicate polio took the shape of the 'Pulse Polio' initiative that started from Tamil Nadu, Kerala and Delhi. The strategy involved the mass immunisation of a target population of children up to five years of age, on pre-arranged immunisation days. In January 1997, health workers vaccinated 127 million children on a single day. The following year another 134 million were vaccinated on the designated day.

Actor Amitabh Bachchan and several other celebrities were roped in to popularise the programme. The government regularly ran advertisements in print media and the radio convincing people to take the vaccine. On March 27, 2014 the WHO declared India a polio-free country. "Micro-planning at the local level, designing strategies for diverse geographic and religious-cultural determinants, and a dedicated technical arm including a highly skilled human resource base in the form of the National Polio Surveillance Project are some of the key strategies that benefited the immunisation programme against Polio," says Rajib Dasgupta, professor at the center for social medicine and community health in Jawaharlal Nehru University (JNU). Bhattacharya says one of the key lessons taught to us by the polio vaccination drive is community health worker based mobile vaccination scheme with effective cold chain. Speaking about how it can be replicated in the vaccination campaign against Covid 19 he says, "community health workers like the ASHA workforce must be trained and given PPE so that they can do home-to-home vaccination."

Lahariya, however, cautions against the home-to-home vaccination which was possible in case of the polio drive. "Injectable vaccines must never be given door-to-door. Firstly, the vaccines have to be stored in controlled temperatures which becomes difficult in such a campaign. Secondly, every person getting the dose has to be watched for at least 30 minutes, which again is difficult in this case," he says. "The eradication drives against smallpox and polio on one hand, and the vaccination campaign against Covid-19 are very different from each other. The former ones were global goals that entailed coordinated action across countries with a strong component of WHO and other international oversight as well as support mechanisms," says Dasgupta. "Covid-19 vaccination has no such goal. Each country is scrambling to protect as much of their population as possible in a supply constrained situation," he adds. At the same time he maintains that the fundamentals of immunisation in India have been shaped by these previous programs. He explains that in the case of smallpox and polio vaccine drives, there was a strong national component, a very capable state and district level leadership and a synergy between these. "It is this synergy which is missing in case of the ongoing drive," he says. Further reading Fractured states: Smallpox, public health and vaccination policy in British India, 1800-1947 by Sanjoy Bhattacharya, Mark Harrison and Michael Worboys Expunging Variola: The control and eradication of smallpox in India (1947-1977) by Sanjoy Bhattacharya War against Smallpox: Edward Jenner and the global spread of vaccination by Michael Bennett Fallacy, sacrilege, betrayal and conspiracy: the cultural construction of opposition to immunisation in India' by Niels Brimmes A brief history of vaccines and vaccination in India by Chandrakant Lahariya Intimidation, coercion and resistance in the final stages of the South Asian smallpox eradication campaign, 1973-1975 by Paul Greenough |

| You are subscribed to email updates from "polio history" - Google News. To stop receiving these emails, you may unsubscribe now. | Email delivery powered by Google |

| Google, 1600 Amphitheatre Parkway, Mountain View, CA 94043, United States | |

Comments

Post a Comment