You can’t get the flu from a flu shot. Here’s why. - The Washington Post

You can’t get the flu from a flu shot. Here’s why. - The Washington Post |

| You can’t get the flu from a flu shot. Here’s why. - The Washington Post Posted: 26 Sep 2020 05:00 AM PDT  One of the common myths that leads people to avoid the flu shot is that they think the shot will give them the flu. But that is simply not true. The virus in the vaccine is not active, and an inactive virus cannot transmit disease. What is true is that you may feel the effects of your body mounting an immune response, but that does not mean you have the flu. I am a nursing professor with experience in public health promotion, and I hear this and other myths often. Here are the facts and the explanations behind them.

Inactive virusInfluenza, or the flu, is a common but serious infectious respiratory disease that can result in hospitalization or even death. The CDC estimates that during a "good" flu season, approximately 8 percent of the U.S. population could get the flu. That is roughly 26 million people. Each year the flu season is different, and the flu virus also affects people differently. One dangerous complication of the flu is pneumonia, which can result when your body is working hard to fight the flu. This is particularly dangerous in older adults, young children, and those whose immune systems aren't working well, such as those receiving chemotherapy or transplant recipients. Historically, millions of Americans get the flu each year, hundreds of thousands are hospitalized and tens of thousands of people die of flu-related complications. During the 1918 flu pandemic, one-third of the world's population, or about 500 million people, were infected with the flu. Since that time, vaccine science has dramatically changed the impact of infectious diseases. The cornerstone of flu prevention is vaccination. The CDC recommends that everyone 6 months of age and older who does not have contraindications to the vaccine, receive the flu shot. And just as the polio vaccine won't give a child polio, the flu vaccine will not cause the flu. That's because the flu vaccine is made with inactive strains of the flu virus, which are not capable of causing the flu. That said, some people may feel sick after they receive the flu shot, which can lead to thinking they got sick from the shot.

Why you might feel offBut feeling under the weather after a flu shot is actually a positive. It can be a sign that your body's immune response is working. What happens is this: When you receive the flu shot, your body recognizes the inactive flu virus as a foreign invader. This is not dangerous; it causes your immune system to develop antibodies to attack the flu virus when exposed in the future. This natural immune response may cause some people to develop a low-grade fever, headache or overall muscle aches. These side effects can be mistaken for the flu but are likely the body's normal response to vaccination. And the good news is these natural symptoms are short-term side effects compared to the flu, which can last much longer and is more severe. It is estimated that less than 2 percent of people who get a flu shot will develop a fever. Also, people often confuse being sick with a bad cold or stomach flu with having influenza. Influenza symptoms can include a fever, chills, sore throat, runny or stuffy nose, body aches, fatigue and headaches. Cold symptoms can be similar to the flu but are typically milder. The stomach flu, or gastroenteritis, can be caused by several different bacteria or viruses. Symptoms of gastroenteritis involve nausea, vomiting and diarrhea.

Preshot exposuresSome people do get the flu after they have received a flu shot, but that is not from the shot. It can happen for a couple of reasons. First, they could have been exposed to the flu before they had the shot. It can take up to two weeks after receiving the flu shot to develop full immunity. Therefore, if you do get the flu within this period, it is likely that you were exposed to the flu either before being vaccinated or before your full immunity developed. Second, depending on the strain of the flu virus that you are exposed to, you could still get the flu even if you received the vaccine. Every year, the flu vaccine is created to best match the strain of the flu virus circulating. Therefore, the effectiveness of the flu vaccine depends on the similarity between the virus circulating in the community and the killed viruses used to make the vaccine. If there is a close match between the two, then the effectiveness of the flu vaccine will be high. If there is not a close match, however, the vaccine's effectiveness could be reduced. Still, it is imperative to note that even when there is not a close match between the circulating virus and the virus used to make the vaccine, the vaccine will still lessen the severity of flu symptoms and also help prevent flu-related complications. Bottom line: You cannot get influenza from getting the flu vaccine. As someone who has treated many people who do get the flu, I strongly urge you to get the shot. Libby Richards is associate professor of nursing at Purdue University. This report was originally published on The Conversation.com. |

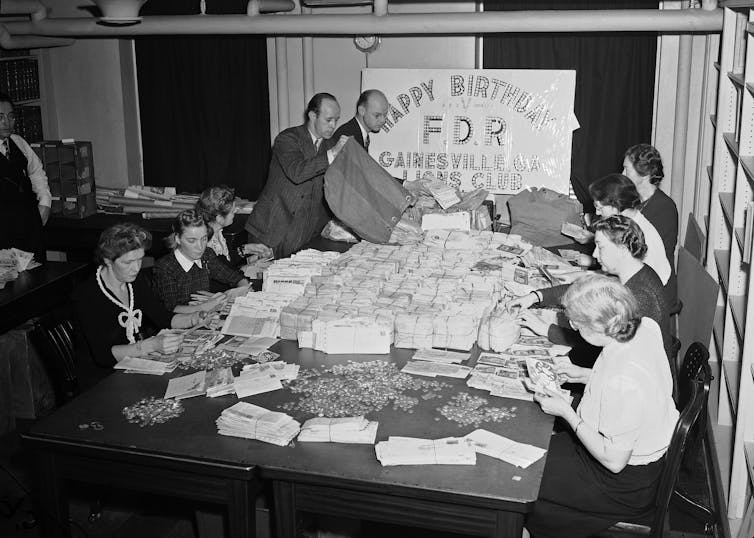

| Posted: 16 Sep 2020 12:00 AM PDT In 1955, after a field trial involving 1.8 million Americans, the world's first successful polio vaccine was declared "safe, effective, and potent." It was arguably the most significant biomedical advance of the past century. Despite the polio vaccine's long-term success, manufacturers, government leaders and the nonprofit that funded the vaccine's development made several missteps. Having produced a documentary about the polio vaccine's field trials, we believe the lessons learned during that chapter in medical history are worth considering as the race to develop COVID-19 vaccines proceeds. Sabin and SalkToday, many competing efforts are underway to create a coronavirus vaccine, each employing different methods to generate the production of universally needed antibodies. Likewise, in the 1950s there were different approaches to making a polio vaccine. The prevailing medical orthodoxy, led by Dr. Albert Sabin, held that only a live-virus vaccine, which involved using a weakened form of the polio virus to stimulate antibodies, could work. That theory stemmed from work by the physician Edward Jenner, who in the 1700s determined that milkmaids exposed to the cowpox virus-laden pus of cowpox-infected cattle did not catch smallpox. Smallpox was the deadly pandemic of the era, and this discovery led to a vaccine that brought about the disease's eradication. Jonas Salk, a doctor and scientist based at the University of Pittsburgh, on the other hand, believed a killed virus, which would completely lose its infectious qualities, could still trick the body into creating protective antibodies against the polio virus. A nonprofit organization, the National Infantile Paralysis Foundation, funded and thus directed the polio vaccine quest. Established by President Franklin D. Roosevelt's former law partner, Basil O' Connor, it raised money for polio research and treatment. As part of this fundraising effort, Americans were called upon to send dimes to the White House in what became known as the March of Dimes. O'Connor gambled on Salk rather than Sabin. Clinical trialsBy 1953, Salk and his team had shown their experimental vaccine worked – first on monkeys in their lab, then on children who already had polio at the D.T. Watson Home for Crippled Children, and then on a small group of healthy children in Pittsburgh. One of the largest field trials in medical history soon followed. It began on April 23, 1954. Some 650,000 children got the Salk polio vaccine or a placebo, and 1.2 million other kids received no injection but were monitored as an untreated control group. Salk's mentor, University of Michigan virologist Thomas Francis, independently monitored the study. After months of meticulously analyzing data, Francis revealed the results on April 12, 1955 – exactly 10 years after FDR's death and nearly a year after the trial began.  A manufacturing errorWhen asked who owned the patent to his vaccine, Jonas Salk famously replied that it belonged to the people and that patenting it would be like "patenting the sun." President Dwight D. Eisenhower expressed his belief that every child should receive the polio vaccine, without indicating how that would happen. Eisenhower charged Health, Education and Welfare Secretary Ovetta Culp Hobby to work out the details in coordination with Surgeon General Leonard Scheele. Congressional Democrats advocated for a plan that would make the polio vaccine free to everyone, which Hobby rejected as a "back door to socialized medicine." Hobby also insisted that private companies should take care of producing Salk's vaccine, licensing six of them to do so. However, she acknowledged that the government lacked a plan to meet the vast vaccination demand. A black market arose. Price gouging jacked up the cost of a dose of the vaccine, which was supposed to be US$2, to $20. As a result, the well-to-do got special access to a vaccine the public had funded. The hands-off approach changed once reports surfaced that children who had received Salk's vaccine were in the hospital, with polio symptoms. At first, Scheele, the surgeon general, reacted with skepticism. He suggested that those kids might have been infected before vaccination. But once six vaccinated children died, inoculations halted until more information about their safety could be gathered. In all, 10 kids who were vaccinated early on died after becoming infected with polio, and some 200 experienced some degree of paralysis. The government soon determined that the cases in which children became sick or died could be traced back to one of the six companies: Cutter Labs. It had not followed Salk's detailed protocol to manufacture the vaccine, failing to kill the virus. As a result, children were incorrectly injected with the live virus. Inoculation resumed in mid-June with tighter government controls and a more nervous public. In July, Hobby stepped down, citing personal reasons. Eisenhower then signed the Polio Vaccination Assistance Act of 1955, which slated $30 million to pay for vaccines – enough to fund wider public distribution. Within a year, 30 million American kids had been inoculated, and the number of polio cases had fallen almost by half. Heeding a lesson learnedBy 1962, there were fewer than 1,000 cases of polio in the U.S. And by 1979, the U.S. was declared polio-free. Years after the vaccine's development, Jonas Salk would recount that sometimes he would meet people who would not even know what polio was – which he found tremendously gratifying. But the events of this past year, with all the ups and downs of coronavirus vaccine research, have proved that the history of polio's defeat is worth remembering. Nine companies developing a coronavirus vaccine recently joined forces to jointly promise that they would not rush anything to market until and unless the clearly delineated standards for safety and efficacy are met. But should a modern-day Cutter incident happen again with a coronavirus vaccine, the public's already shaky faith in vaccines could easily crumble further, impeding the effort to get as many people quickly immunized against COVID-19 as possible. [Deep knowledge, daily. Sign up for The Conversation's newsletter.] Bringing this pandemic to an end will require more than the government's approval of one or more coronavirus vaccines that work. Coordinating a widespread vaccination campaign will also demand the navigation of logistics, economics and politics amid an equitable approach to the distribution of these new vaccines and the public's willingness to be inoculated. This final push will, in addition, require the often uneasy partnership among the government, the private sector and – as is true today with massive contributions from the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation and other charitable sources – philanthropy. |

| You are subscribed to email updates from "poliomyelitis symptoms" - Google News. To stop receiving these emails, you may unsubscribe now. | Email delivery powered by Google |

| Google, 1600 Amphitheatre Parkway, Mountain View, CA 94043, United States | |

Comments

Post a Comment