Timeline: Do vaccines really work? | World – Gulf News - Gulf News

Timeline: Do vaccines really work? | World – Gulf News - Gulf News |

| Timeline: Do vaccines really work? | World – Gulf News - Gulf News Posted: 14 Jul 2020 05:39 AM PDT  Highlights

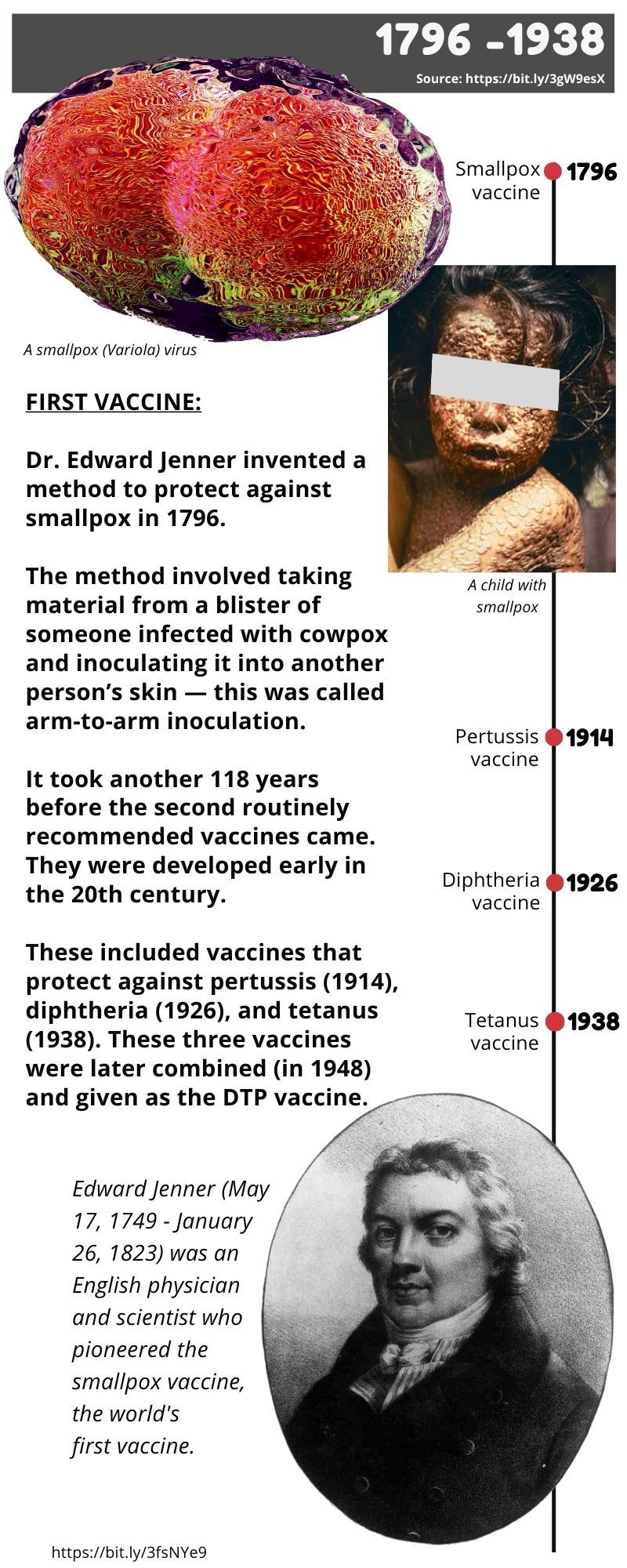

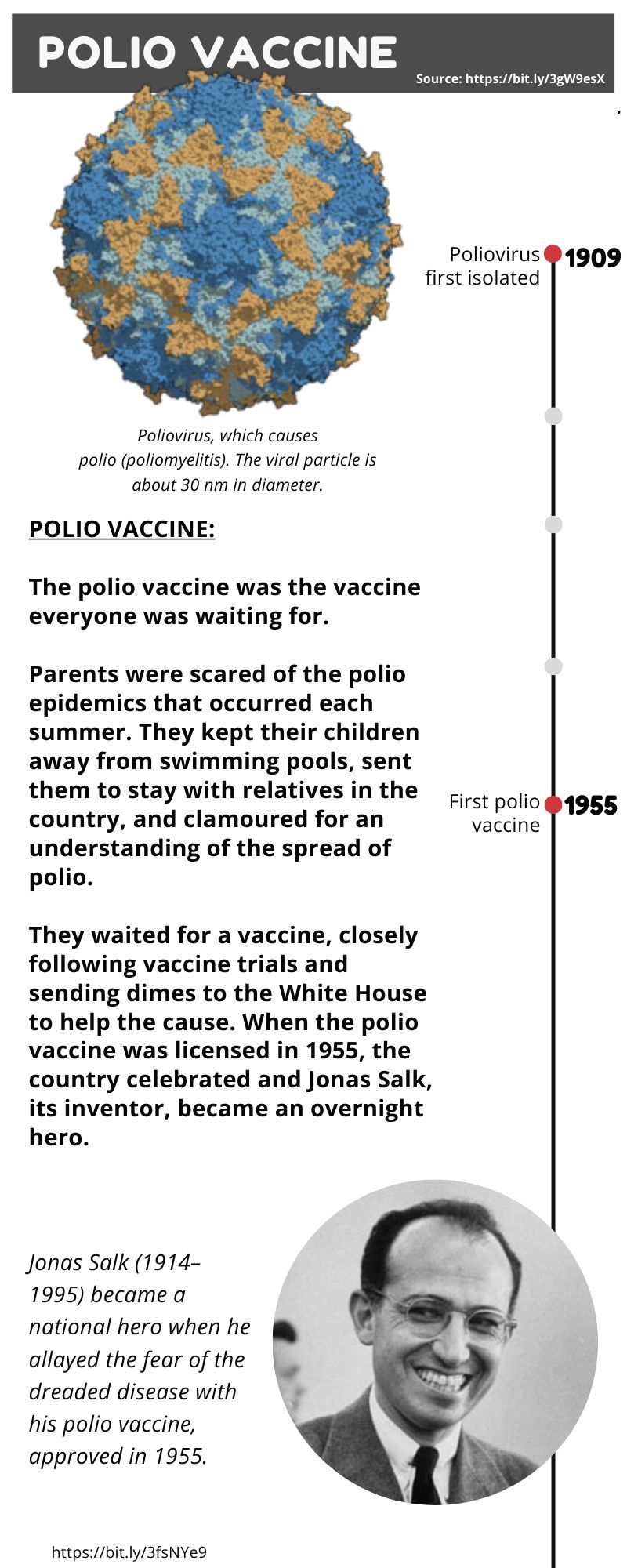

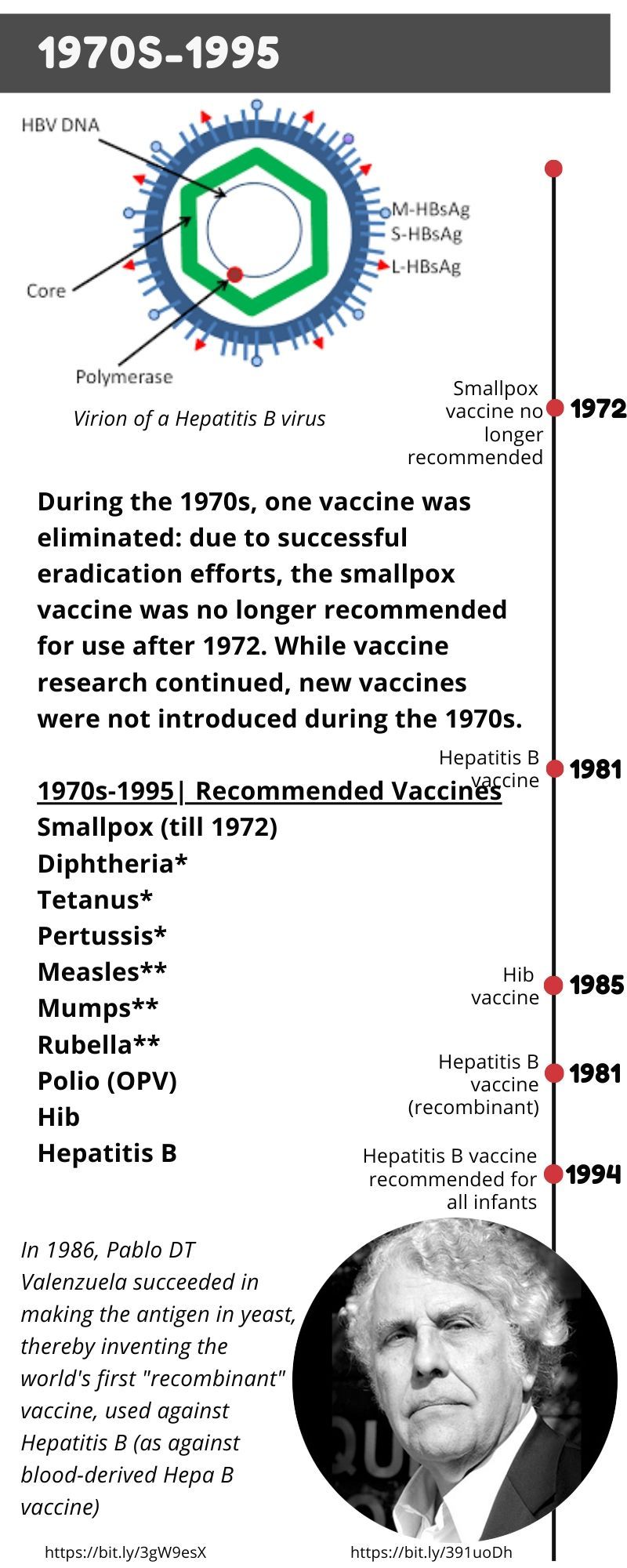

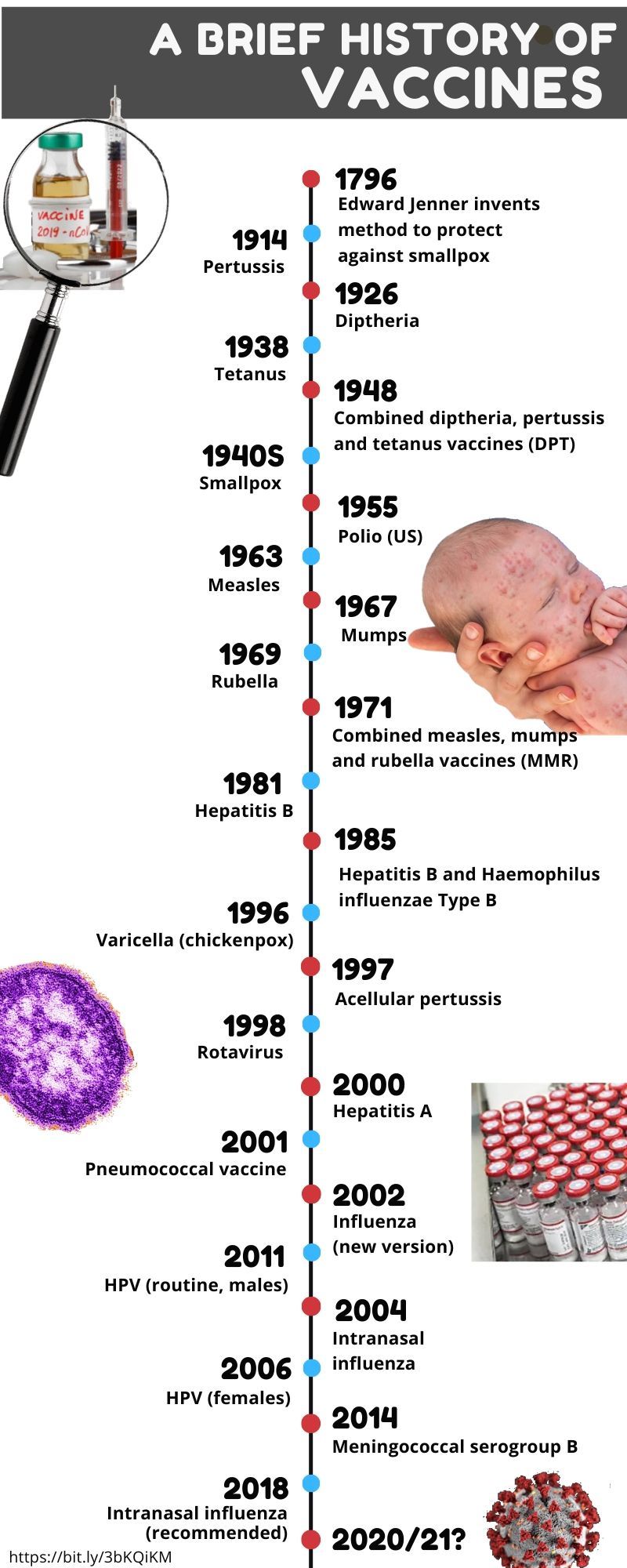

DUBAI: Scientists have accumulated a whole body of knowledge since Edward Jenner came up with the smallpox vaccine. The result: faster pace of vaccine development. But it's not been a straight line. More like stocks, with ups and downs, but generally an upward movement, in both speed and numbers. Some have bombed. The first hurdle, of course, is that no two pathogens are the same. And tThere are billions of them, of which the great majority are harmless to man. Some bacteria are actually good, so you don't want to kill them all. From the first vaccine in 1796 to the present, scientific knowledge had developed enough, so that large-scale vaccine production and distribution are possible. Today, there are at least 26 vaccines listed by the World Health Organisation (WHO). There are dozens more in the pipeline. Now the questions must be asked: Q: Do vaccines really work?Yes, they do. If they didn't, we'd still see lots of people, especially youngsters, crippled by polio, or afflicted with smallpox, measles, and other childhood diseases. With transcontinental travel (especially before COVID-19), these diseases would have easily crippled the world without a vaccine for them. These diseases had been virtually eradicated today, thanks to billions of vials of good vaccines that had been produced over the last few decades. Vaccine development is both science and miracle: Each jab injects a version of a disease-causing foreign body into the human body to stimulate the production of antibodies that then fight off a version of same disease-causing foreign body. Q: Why is SARS-CoV-2 more "efficient" in spreading, compared to SARS/MERS/Ebola, even if they're from the same virus (coronavirus) family?No two viruses are the same. Scientists point to the fact that SARS-CoV-2's efficiency in infecting people around the world on one fact — the period of viral "shedding" (top transmissibility, or infectiousness) happens between Day 1 to Day 7, when carriers don't even display symptoms yet. For example, in March 2020, German researchers found very high levels of the COVID-19 virus emitted from the throat of patients from the earliest point in the illness. That's the point at which people are generally still going about their daily routines. Without basic hygiene practices, no mask, no handwashing, it's a losing game for everyone. There's also the challenge with tests (either not available or unreliable). A combination of good hygiene practices, social distancing, understanding this "mechanism of attack", alongside the introduction of a vaccine or therapy against it (all still in development) would usher in a major pushback against the virus. Q: When was the first vaccine produced?Q: What happened then?In 1976, Dr. Edward Jenner, an English physician and inventor, developed a method to protect against smallpox. The method involved taking material from a blister of someone infected with cowpox and inoculating it into another person's skin. It was called arm-to-arm inoculation.  Q: How long does it typically take to develop a vaccine?In the case of smallpox, it took millennia, since it's the first vaccine known to man. The rhythm of development has gathered pace, though development was not a straight line. There was vaccine fiascos that happened along the way, but these gave scientists and regulators better understanding of the challenges. The fastest vaccine to be developed was the Measles vaccine, which took five years (1963 to 1968), but the development started in earnest in 1953. Therefore, it still took a full decade (10 years) from the time John F. Enders and Dr. Thomas C. Peebles collected blood samples from several ill students during a measles outbreak (in Boston), to the year (1963) the B strain of measles virus was turned a vaccine and licensed. The poliovirus, which causes poliomyelitis (polio) was first isolated in 1909. The first polio vaccine camne out in 1955. With the COVID-19, most scientists say it's between 12 to 18 months, including the three-phase clinical trials, review, licensing and mass production. US President Donald Trump's so-called "Operation Warp Speed" aims for a much earlier target for developent, certification, production and distribution.  Q: What are the vaccines available today?The Who lists more than 20 available or recommended vaccines:

Q: How many types vaccines are there?Vaccines are produced depending on their type, of which there are currently 6:

In most vaccine platforms, the serum comes from the whole virus, or a version of it. It is cultured and processed/mass produced in a high-security biosafety facility. They are then stored in vials that end up being injected into our arms (or taken orally, as in the case of the $0.50 oral polio virus, OPV). In effect, the dose injected to us (determined after careful, extensive trials) gets us "infected", which then triggers an immune response in our body. That's how immunity is achieved. After the shot, our body will just shrug off the disease-causing infection the moment we get it — often without us even know about it. In biology, it immunity refers to he ability of an organism (man) to resist a particular infection (SARS-CoV-2) or toxin by the action of specific antibodies, or sensitised white blood cells. Q: If a vaccine is taken from the same pathogen that causes the disease, why are vaccines difficult to develop?So we already know that vaccines do work. But, there are too many viruses swirling around us. We don't know which one will hit us next. For most vaccines against emerging infectious diseases, the main challenge is not the vaccine effectiveness itself. Rather, it's the extensive trials or tests needed to ensure the dosage people by the hundreds of millions get is both safe and effective. So there's a constant war between safety/efficacy and immediacy.  GLOSSARY: VECTOR A vector refers to an organism (insect, tick or virus), that transmits a disease from one animal or plant to another. In molecular biology, a vector is a DNA molecule used as a vehicle to artificially carry foreign genetic material into another cell, where it can be replicated and/or expressed (e.g., plasmid, cosmid, Lambda phages). Of these, the most commonly used vectors are plasmids. Viral vectors are tools commonly used by molecular biologists to deliver genetic material into cells. This process can be performed inside a living organism or in cell culture. Viruses have evolved specialised molecular mechanisms to efficiently transport their genomes inside the cells they infect. Q: What the 'anti-vaccine' movement?There are studies of social networks which show that opposition to vaccines is small but far-reaching — and growing. Nature wrote about a "small but fervent anti-vaccination movement" that's organising against it a COVID-19 shot. Campaigners are seeding outlandish narratives: they falsely say that coronavirus vaccines will be used to implant microchips into people, for instance. They also made false claims that a woman who took part in a UK vaccine trial "died". In April, some carried placards with anti-vaccine slogans at rallies in California to protest against the lockdown. There's a now-deleted YouTube video promoting wild conspiracy theories about the pandemic and asserting (without evidence) that vaccines would "kill millions" received more than 8 million views. Nobody knows how many people would actually refuse a COVID-19 vaccine. Q: What vaccines are in the pipeline?The WHO lists the following vaccines under different stages of development:

|

| You are subscribed to email updates from "poliomyelitis causes" - Google News. To stop receiving these emails, you may unsubscribe now. | Email delivery powered by Google |

| Google, 1600 Amphitheatre Parkway, Mountain View, CA 94043, United States | |

Comments

Post a Comment