Who created the polio vaccine? - Livescience.com

Who created the polio vaccine? - Livescience.com |

- Who created the polio vaccine? - Livescience.com

- Polio, coronavirus draw eerie, similar parallels - cleveland.com

- Polio perspective - Sussex Countian

- Pandemic has powerful resonance for Colorado Springs polio survivor - Colorado Springs Gazette

- Researchers suggest oral polio vaccine be tested to see if it might help against SARS-CoV-2 - Medical Xpress

| Who created the polio vaccine? - Livescience.com Posted: 01 Jun 2020 12:00 AM PDT In the early 1950s, two prominent medical researchers each found a way to protect the world from poliomyelitis, the paralysis-causing disease commonly known as polio. The vaccines created by Dr. Jonas Salk and Dr. Albert Sabin resulted in the near-global eradication of polio. Here's how they did it. What is polio?Polio is a disease caused by three variants of the poliovirus, according to a 2012 review written by microbiologist and polio expert Anda Baicus and published in the World Journal of Virology. The virus, which only infects humans, can damage the neurons that control movement, resulting in partial or complete paralysis. A person can become infected with the virus by consuming contaminated food or water, or by allowing contaminated items (such as dirty hands) to touch or enter the mouth, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Studies of Egyptian mummies suggest that polio affected children at least as early as ancient times, but the U.S. didn't experience its first polio epidemic until the late 1800s. In the U.S. in 1916, more than 27,000 people were paralyzed by the disease and at least 6,000 people died from it, according to History.com. For the next several decades, the epidemic expanded throughout the U.S. and Europe. In 1952 alone, there were 58,000 new cases of polio and 3,000 deaths from the disease in the U.S. Related: The 12 deadliest viruses on Earth As medical experts worked to understand the virus, they discovered that it could infect people without causing symptoms. In a 1947 study published in the American Journal of Hygiene, researchers reported that the prevalence of poliovirus in New York City sewage water meant that there were an estimated 100 asymptomatic cases of polio for every symptomatic, or paralytic, case of the disease at the time. Today, more recent research suggests that 72 out of 100 people who are infected with the virus will never experience symptoms, and about 1 in 4 infected people will experience only flu-like symptoms that last between 2 and 5 days before going away on their own, according to the CDC. In the late 1930s, researchers learned that infected individuals shed the virus in feces for several weeks, whether or not they had symptoms of the disease. Researchers have since confirmed that infected, but asymptomatic, people can still shed the virus and make people sick. People who do become sick can shed the virus immediately before they show symptoms and for up to 2 weeks after their symptoms appear, according to the CDC. Development of the Salk vaccineResearchers began working on a polio vaccine in the 1930s, but early attempts were unsuccessful. An effective vaccine didn't come around until 1953, when Jonas Salk introduced his inactivated polio vaccine (IPV). Salk had studied viruses as a student at New York University in the 1930s and helped develop flu vaccines during World War II, according to History.com. In 1948, he was awarded a research grant from President Franklin D. Roosevelt's National Foundation for Infantile Paralysis, later named March of Dimes. Roosevelt had contracted polio in 1921 at age 39, and the disease left him with both legs permanently paralyzed. In 1938, five years into his presidency, Roosevelt helped to create the National Foundation for Infantile Paralysis to raise money and deliver aid to areas experiencing polio epidemics.

Thanks to the work of researchers before him, Salk was able to grow poliovirus in monkey kidney cells. He then isolated the virus and inactivated it with formalin, an organic solution of formaldehyde and water that is commonly used as a disinfectant and embalming agent. A similar procedure had been tested years prior, in 1935, by American scientist Maurice Brodie, in which he extracted poliovirus from live monkey spinal cord tissue and then suspended the virus in a 10% formalin solution, polio expert Baicus wrote. Brodie tested his vaccine on 20 monkeys and then on 300 schoolchildren, but the results were poor and Brodie didn't test any further. Related: 5 dangerous myths about vaccines Salk's vaccine was unusual because instead of using a weakened version of the live virus, such as what is used for mumps and measles, Salk's vaccine used a "killed," or inactivated, version of the virus. When the "dead" poliovirus is injected into the bloodstream, it can't cause an infection because the virus is inactive; but the immune system can't distinguish an activated virus from an inactivated one, and it creates antibodies to fight the virus. Those antibodies persist and protect the person from future poliovirus infection. In 1953, Salk began testing his inactivated polio vaccine (IPV) on a small number of former polio patients in the Pittsburgh area and on himself, his wife and their three sons. The initial results were promising, and he announced his success on the CBS national radio network on March 25, 1953, according to History.com. He became an instant celebrity.

The first large-scale clinical trial of Salk's vaccine began in 1954 and enrolled more than 1 million participants. It was the first vaccine trial to implement a double-blind, placebo-controlled design — now a standard requirement in the modern era of vaccine research, according to Arnold S. Monto's 1999 review published in the journal Epidemiological Reviews. The scientist leading the vaccine trial, Dr. Thomas Francis, Jr. from the University of Michigan, announced the positive results at a press conference on April 12, 1955. Later that same day, the U.S. government declared Salk's vaccine safe and effective for use, according to The College of Physicians of Philadelphia's History of Vaccines. Related: 20 of the worst epidemics and pandemics in history After the press conference, CBS reporter Edward R. Murrow asked Salk who owned the vaccine. "Well the people, I would say," Salk famously answered. "There is no patent. Can you patent the sun?" Salk never patented his vaccine. Only a few weeks later, reports began surfacing of children experiencing paralysis after receiving the vaccine. More than 250 new polio cases were traced back to batches of the vaccine made by Cutter Laboratories, according to the CDC. The batches had contained live, active strains of poliovirus. The U.S. Surgeon General halted all polio vaccine administration until all manufacturers could be investigated and verified for safety. At the time, there had been little government regulation over vaccine manufacturers, but that quickly changed after what is now known as the Cutter Incident. Since then, not a single case of polio has ever been attributed to the Salk vaccine. Sabin's oral polio vaccineWhile Salk was developing his inactivated polio vaccine, his professional rival, virologist Dr. Albert Sabin at the University of Cincinnati, was working on a vaccine made with active, but weakened, virus. Sabin opposed Salk's vaccine design and considered an inactivated virus vaccine to be dangerous. By 1963, Sabin had created an oral live-virus vaccine for all three types of poliovirus that was approved for use by the U.S. government. Sabin's version was cheaper and easier to produce than the Salk vaccine, and it quickly supplanted the Salk vaccine in the U.S. In 1972, Sabin donated his vaccine strains to the World Health Organization (WHO), which greatly increased the vaccine's availability in low-income countries.

Sabin's oral polio vaccine (OPV) was critical for helping to decrease the number of polio cases globally, but unlike the Salk vaccine — which carries no risk of paralysis — the OPV carries an extremely small risk of causing paralysis. Today, the WHO estimates that about 1 in 2.7 million doses of OPV result in paralytic polio. Related: 5 deadly diseases emerging from global warming Since 2000, Salk's inactivated polio vaccine is the only version administered in the U.S., in order to avoid any risk of vaccine-induced polio associated with OPV. The OPV is still administered in many parts of the world, but the WHO's Global Polio Eradication Initiative aims to cease the administration of OPV altogether once wild (non vaccine-related) polio is completely eradicated. The CDC now recommends children receive four doses of IPV, one each at ages 2 months, 4 months, between 6 and 18 months, and between 4 and 6 years. Thanks to widespread use of the polio vaccine, the U.S. has been polio-free since 1979. Globally, cases of polio due to wild poliovirus have decreased by 99% since 1988, according to the WHO, from an estimated 350,000 cases per year to just 33 new cases in 2018. Additional resources: |

| Polio, coronavirus draw eerie, similar parallels - cleveland.com Posted: 08 Jun 2020 02:43 AM PDT CLEVELAND, Ohio - A virus ravages the nation, media reports tally daily numbers, quarantines are ordered and restrictions on public gatherings are called for - and opposed by some. It hits urban and rural areas, rich and poor. Fundraisers are held to raise money to seek a cure. And it's not coronavirus. It was polio in the late 1940s and '50s. Just as doctors, scientists, pharmaceutical companies and other firms scramble to understand this strain of coronavirus, the medical community more than half a century ago was doing the same. In 1949, John A. Toomey, head of the department of contagious diseases at City Hospital in Cleveland, assessed polio as stubborn and said symptoms were not too well defined - one contrast to today, as the Centers for Disease Control has listed several symptoms connected to coronavirus. At least one point Toomey made turned out to be patently untrue. "Polio has not been proved to be contagious," said Toomey, whose spoke on a local radio station. (The Spanish flu that ravaged the world in 1918 had residents wearing masks, but face coverings did not appear to be in widespread use in the 1940s and '50s for polio.)  A doctor spoke on the radio in Cleveland in 1952 questioning whether polio was contagious. "Influenza dates back to biblical times - but not polio which is relatively new and which is increasing," Toomey said. He added prevention lies in "hygiene" and people should avoid swimming "in the polio season," which was seen as late July to November. He spoke a day before 17 people were admitted to City Hospital for polio. Polio, paralysis and a president Polio - Poliomyelitis - is derived from Greek words for "gray" and "marrow." What was known as "infantile paralysis" could be transmitted through coughing, sneezing and feces. The virus could enter through the mouth but grow in the digestive tract. In many cases, the infected person showed no symptoms. But paralysis could, for a fraction of those infected, set in. Of those victims, up to 10 percent died when their muscles for breathing became paralyzed. Polio, which took six to 20 days to incubate, stayed contagious for as many as two weeks. It did not discriminate. While it often affected children, nothing else mattered: Wealthy and impoverished people in rural, urban and suburban areas all contracted polio. Unlike coronavirus, whose seasonal tendencies are still being analyzed, polio hit in late summer and early fall. And while coronavirus deaths have claimed people notable in their fields - musician Joe Diffie, playwright Terrence McNally, to name two - the face of polio could not have been a more prominent one. President Franklin Roosevelt contracted polio at age 39. It was Roosevelt who founded the National Foundation for Infantile Paralysis in 1938, during his second term. Roosevelt used to hold "Birthday Balls" to raise money for a cure and patient care.  President Franklin Roosevelt founded the National Foundation for Infantile Paralysis in 1938.ASSOCIATED PRESS That awareness and organized fundraising promotion came years after the first polio epidemic in the United States, which occurred in Vermont in 1894, with 132 cases and 18 deaths. In 1916, the first large epidemic on American soil was felt in the same place coronavirus would later slam - New York City. The city reported 2,343 deaths and more than 9,000 cases. That year, 27,000 cases and 6,000 deaths were reported across the country. Outbreaks became a regular occurrence. Iron lungs, imposing torpedo-tube-like structures surrounding a person, became a fabric of hospital wards. It is believed only two people in the United States use an iron lung today. With the introduction of a vaccine in 1952, cases began to tail off considerably. And in 1961, Albert Sabin developed an oral polio vaccine. (In Cleveland, "Sabin Oral Sundays," were held. Physicians and volunteers distributed vaccine-infused sugar cubes and immunized more than 84% of Cuyahoga County residents, the best record in the United States. The success rate is attributed to "voluntary action, advertising, and public-relations expertise from the nonmedical community," according to the Encyclopedia of Cleveland History.) From bad (scam artists) to good (fundraising) The viruses share an unfortunate, unscrupulous bond. Like scam artists now misrepresenting masks, which turn out to be inferior, polio also was not immune to similar schemes. Some companies began selling "polio insurance," which was derided by a Cuyahoga County official with the National Foundation for Infantile Paralysis as "hitting below the belt." In 1954, a former Dayton cosmetics manufacturer, Duon H. Miller, headed an organization that opposed mass inoculations. Miller, who had been cited by Better Business Bureaus in the past, claimed soda caused polio. Ironically, on the same day the press reported about Miller's literature campaign, "The Eddie Cantor Story" was playing in local theaters.  A polio ward in an Akron church basement for Akron Children's Hospital in 1952. (Cleveland Memory Project, Cleveland State University, Michael Schwartz Library, Special Collections) The irony is that Cantor promoted a wide-scale philanthropic media effort to ignite fundraising for Roosevelt's efforts. Cantor had riffed on news reports of the day called "The March of Time." In radio broadcasts and newsreels, he encouraged a "March of Dimes," based on the notion that almost anyone could afford to donate a dime. In January 1938, he urged folks to pony up. His hope was a million people each would send a dime to raise $100,000 to fight polio. Countless envelopes containing the Winged Liberty Heads were mailed to Washington, D.C. Within weeks, $8,000 had been raised. The White House received 2,680,000 dimes, or $268,000. The National Foundation for Infantile Paralysis would become March of Dimes. Roosevelt's profile would replace the Winged Liberty image in 1946, a year after his death. The campaign and the organization were necessary ammunition in the fight against polio. In 1952, the disease ravaged Cleveland, Ohio and the country. A record 57,628 cases were reported nationally. In Northeast Ohio, Eastlake tavern owner Lloyd Culp grew a full, 19th-century-looking beard - rare for 1952, common today - and wagered he would not shave until the Cleveland Indians won a pennant. He wore the beard for 20 months, lost the bet, and donated $400 to a polio benefit party at his bar, Culp's Bend Night Club. A grinning Culp also auctioned his cut whiskers for $145. If he could have held out for two more seasons, he would have won. Coverage of polio Safety vs. business also became a lightning rod. In September 1952, Delmar A. Canaday, mayor of Pomeroy on the West Virginia border, decided to end his 10-day ban on public gatherings three days early, affecting churches, schools and taverns. Dr. Frederick H. Wentworth, chief of communicable diseases at the state health department, agreed, saying mass quarantines would not help stem the spread of the virus and closing schools was "most ridiculous of all." Meigs County prosecutor John C. Bacon weighed in, saying the county health department should determine closures and reopenings.  Polio fundraisers and photo opps were common more than half a century ago.AP In 1949, a medical professionals group came out opposed to isolating people. "Quarantine does no known good in halting the spread of polio" read the lead paragraph of a 1949 Plain Dealer story that went on to say "the mere posting of quarantine signs" was frightening and burdensome. The group also opposed the closure of public gathering places - theaters, pools, fairs. Ironically, that Page One account in Cleveland ran a few columns over from a story on the death of Lt. Robert D. Prendergast of the Army Medical Corps. The Lakewood man who had attended St. Ignatius High School and John Carroll University was diagnosed on Aug. 19 and dead 48 hours later. Newspapers were filled with short and long stories, much like media accounts peppering the internet. Coverage reads like health-department statistics being Tweeted. But instead of anonymous numbers, names were often reported. On Aug. 8, 1952, two married women - one mother of three, another a mother of two - were among six cases reported in Cleveland. Betty Labuda of Parma and Marguerite Elikofer were listed in City Hospital. They were among 174 cases in Northeast Ohio - 63 in Cleveland, 86 in Cuyahoga County outside of Cleveland, and 25 outside of Cuyahoga County. At the end of August, Summit County reported that 122 people were hospitalized - 14 critical - and 26 people had died. March of Dimes drives continued to be held. Jane Lausche, wife of Ohio Gov. Frank Lausche, former mayor of Cleveland, headed up a "mothers' march" on polio in the city. Skateland Roller Rink at E. 90th Street and Euclid Avenue, now the heart of Cleveland Clinic's campus, held fundraisers, with one themed "Let's skate that others may walk." "Parents were frightened to let their children go outside, especially in the summer when the virus seemed to peak," according to Centers for Disease Control. "Travel and commerce between affected cities were sometimes restricted." Quarantines were common. The rear-view mirror vantage of polio shows a disease of the past, thanks to vaccines and time, but it remains a pertinent generational glimpse as coronavirus grips the nation. The United States has been polio-free since 1979. Related coverage We've been here before: How Cleveland survived the 1918 Spanish flu, compared to coronavirus Remember quarantines of days gone by Sources (The online links here are to specific pages for more reading on polio.) The Plain Dealer, Encyclopedia of Cleveland History, United Health Rankings, Centers for Disease Control, BBC, The History of Vaccines and The Guardian. I am on cleveland.com's life and culture team and cover food, beer, wine and sports-related topics. If you want to see my stories, here's a directory on cleveland.com. |

| Polio perspective - Sussex Countian Posted: 03 Jun 2020 12:00 AM PDT Survivors see similarities in virus outbreaks The coronavirus pandemic is the first virus many Americans have seen that has caused widespread fear, but it brings back memories for others. John Nanni of Middletown and Alex Vaughan of Dover are polio survivors. Diagnosed with the life-threatening disease before age 2, both have lived through the panic caused by polio and now COVID-19. From closing schools to waiting for a vaccine, Nanni and Vaughan see many similarities and differences between the country's reaction. Surviving polio In 1953, Nanni was 10 months old and living in Binghamton, New York when he was diagnosed with polio, which paralyzed him from the neck down. His mother gave him physical therapy, so his muscles wouldn't atrophy. His mother's efforts helped him walk again. Nanni survived the virus, but his struggles didn't end. Growing up, he was physically weaker and slower than the rest of the kids his age. Although he struggled, he knows he is one of the lucky ones. "I've been very blessed. If I was born in a developing country, I wouldn't be here today," Nanni said. Over the years, he has experienced post-polio syndrome — a condition that causes muscle weakness, fatigue and joint pain in polio survivors — but the 67-year-old still lives a full life. Nanni is the president of the Middletown-Odessa-Townsend Rotary Club and Rotary District 7630 PolioPlus committee chair for Delaware and Eastern Shore Maryland. In these roles, he has spent part of his adulthood learning about the outbreak and helping eradicate polio around the world. Just like Nanni, Vaughan's mother was one of the reasons he was able to survive. Vaughan said he was always an active child. When he was 18 months old, his mother began to notice he wasn't walking around the house as much as he used to. He was diagnosed with polio, which stunted growth in his right leg. He said most medical professionals in his community didn't know the proper way to treat the virus, but the common consensus was rest and inactivity. Vaughan's mother disagreed. "I know my mother was quite the warrior," he said. "She was one of the first proponents in our circle of friends who used isometrics to help treat me. They had no clue what to do, but she knew sitting still was not the right thing. She kept me active." Vaughan, now 68 years old, is the chief entertainment officer for Affinity Entertainment Delaware and is active in his Rotary Club. Symptomatic or not Like COVID-19, people could be contagious with poliomyelitis before symptoms appeared. Nanni said researchers didn't know why some people who caught the virus had mild symptoms and others had extreme outcomes, including paralysis or death. "It's why polio was so hard to stop," he said. "Back then, they knew less about polio than what they know now about the coronavirus." The poliovirus spreads from person to person, entering the body through the mouth by the sneeze or cough of an infected person or by contact with feces. Polio — which affects the spinal cord, causing paralysis — was once one of the most feared diseases in the U.S. According to the Centers for Disease Control, polio outbreaks in the U.S. increased in frequency and size in the late 1940s and continued throughout the early 1950s. Polio outbreaks caused more than 15,000 cases of paralysis each year until a vaccine was introduced in 1955. Vaughan said panic increased throughout the 40s and 50s, but the virus had been in the U.S. for decades before then. He said media and mass communication had significantly changed — television became a predominant form of media — which allowed more people access to information about polio, how many people had it and what the symptoms were. "We just need to look back and track [mass communication] over history and overlay that with what was happening at that time and how people were reacting to it. It all fits together," he said. About 72 out of every 100 people who get the virus never have visible symptoms, according to the CDC, and about one out of four people who do will have flu-like symptoms. Vaughan said many people thought polio and the flu were the same because it was hard to differentiate between the two unless there was paralysis. COVID-19 has hit all age groups but has affected elderly and those with preexisting conditions the worst. It was possible for all age groups to get polio, but children were infected more often. "To this day, they still don't know why children were susceptible to polio and adults were not, I suspect it was because they put more things in their mouth," Nanni said. Today, hospitals and nursing homes are not allowing unnecessary visits from family members, but this is not unique. "I think it's very similar with polio survivors who are telling their stories about how they felt abandoned when they were in the hospital polio wards," Nanni said. "They went weeks without seeing their parents. When they did, it was from a far distance from behind a glass window." Virus fear COVID-19 has shut down schools, sports, businesses, playgrounds and activities. People saw such closures during the polio outbreak. According to the History Channel, the prevalence of polio in late spring and summer popularized the "fly theory" because most middle-class Americans associated disease with flies, dirt and poverty. The seasonal surge and apparent dormancy in winter matched the rise and fall of the mosquito population. Nanni said public pools, Little League fields and movie theaters were closed, most towns seemed empty and parents stopped taking their children to the grocery store. "There weren't protests. There was a lot of fear," he said. "When [people] had to quarantine, they did quarantine." Vaughan was too young to remember, but his mother told him polio "scared them half to death," but people didn't react in their community the way the country has today. "My parents were in their mid-to-late 20s, and they grew up most of their lives with polio being in their everyday life," he said. "You didn't know who was going to get it. You knew what it might do, but there is no way of knowing if you would get it." Nanni attributes this to limited federal and state government involvement in deciding what should be open and if people should be quarantined. He said communities would decide what should shut down depending on whether their area had a diagnosed case and if they had access to the vaccine. "It was more local government than federal shutting things down," Nanni said. "It was more reactive than preventive." Nanni said the localities did not start to reopen shuttered places until there was a vaccine. Finding a vaccine Researchers and health officials project a COVID-19 outbreak in the fall. The Trump administration announced "Operation Warp Speed" to accelerate vaccine development with the hope of having 300 million doses available by January. Nanni said he is concerned with the country opening up too soon, given the lack of social distancing he still sees. "You see these people on beaches and those protestors who are going around to these state capitol buildings and they are not wearing masks and they are all bunched together," he said. "If you really do any research at all, scientifically, one person can affect so many people." Vaughan said he is hopeful doctors will find a vaccine that will eradicate the coronavirus, just like the one for polio did. Until there is a vaccine, he said people should follow safe practices and use proper caution to keep everyone healthy. "We are in the beginning stages of a disease that might affect people for a generation or more," Vaughan said. "It might just be like polio in the early part of the 20th century. It might be something our people will have to learn to live with. It can hit you or miss you and that's just life." |

| Pandemic has powerful resonance for Colorado Springs polio survivor - Colorado Springs Gazette Posted: 29 Jun 2020 07:27 AM PDT  Carol Todd was almost 8 years old on that sweltering July day in 1948, when her mom took her and her five siblings to cool off at a public pool near their farm in Chandler, Ariz. As usual, when the time came to return home, Todd — who "loved the water and was so stubborn" — was the last one out of the water. She believes that may be the reason she contracted the polio virus, and her brothers and sisters did not. "I guess because I was in the water longer I came into contact with something they didn't, or that came along after they got out," said Todd. "All I know for sure is that I was exposed, and they weren't ... thank God." The chlorine compounds used to sanitize modern pools are strong enough to kill any viruses that might be present, including the coronavirus. But for Todd, within a few days of that fateful swim more than 70 years ago, life-threatening symptoms began to manifest. First, she lost the ability to swallow. Then, to hold her head upright. Her parents rushed her to the doctor, but by the time they arrived she was almost entirely paralyzed and struggling to breathe. The first polio cases in the U.S. were identified in the late 1800s, and over the following 60 years it waxed and waned in public consciousness as periodic spikes led to outbreaks, and more high-profile infections, including that of Franklin D. Roosevelt. Though it's now believed the 32nd president more likely suffered from Guillain–Barré syndrome, he was diagnosed with polio in 1921, at age 39. The illness left him with permanent paralysis from the waist down, and when he entered the White House in 1933, for a record 12-year tenure, he did so by way of specially-installed wheelchair ramps. "I'm sure my mother was aware of polio, and what it could do, but it wasn't something that was on people's minds," said Todd, whose diagnosis was confirmed by spinal tap. "Places weren't shut down like they are now, and information obviously wasn't as available as it is now." Todd contracted bulbar polio, a severe iteration of the virus, which attacks the part of the brain that controls autonomic motor functions, such as breathing. "My pulmonary doctor in the Springs would always shake my hand when I came in and say, 'I've never met a bulbar polio survivor, and certainly none like you,'" said Todd, who was born in Colorado Springs to a homesteading family with deep roots in the Pikes Peak area. After her diagnosis, she was moved to the polio ward at a Phoenix children's hospital, where a mechanical respirator known as an iron lung, the precursor to the modern day ventilator, did the work her lungs no longer could. For nourishment, she was fed eggnog by way of a throat tube, three times a day. For weeks, as her life hung in the balance, she said her mother prayed by her hospital bed. "At one point when there was no hope or improvement, the hospital priest came and gave me last rites," wrote Todd, in an essay describing her survival story for The Gazette. "As he finished praying, a few raindrops fell outside the window on a cloudless day. Mama knew God heard him. The next day, my eyes focused and I moved my arm. From then on, I began to get better. It really was a miracle." The miracle, as it continued to play out, required the devotion of nurses who applied the "Sister Kenny" method, a then-revolutionary and still controversial therapeutic approach developed by Elizabeth Kenny, a self-trained Australian nurse, to help polio victims regain the use of muscles ravaged by the disease. "Three or four times a day, a big tub on a cart would come to each bed. I could smell it coming," wrote Todd. "It was full of hot, wet, steaming, stinking, wool blanket squares (Army type) that the nurse would wrap around my entire body and then cover with canvas strips held tightly with big safety pins. I'd lay there like a mummy for hours, listening to all the kids cry, but I was unable to cry yet." After many months, Todd began to recover, eventually enough to return to her family, where home-based physical therapy — on a budget, using canned vegetables for exercise weights — continued, said Todd, whose family moved back to Colorado Springs in 1950. Four years later, after the polio vaccine developed by Jonas Salk became available, Todd lined up "with millions of others to take it," she wrote. Because of the vaccine, the U.S. has been polio-free since 1979. Todd survived a devastating virus, and though her spine is curved in two places, her ribs deformed and her breathing compromised, she says she hasn't missed much in life. "When life was totally taken away from me, I became determined to never miss out on anything ever again if I got well," wrote Todd. "I've belly-danced, hiked, streaked, skated, skied, partied, raced jeeps on ice, camped, went swimming (still the last one out of the water), hammered, traveled, kissed Elvis, made cement, and served 36 years at HQ NORAD." She also has a message to share, in modern pandemic times. "There's hope to get through a virus. We can get through this, and maybe even find some good on the other side," she said. "I just hope everyone can keep that in mind." |

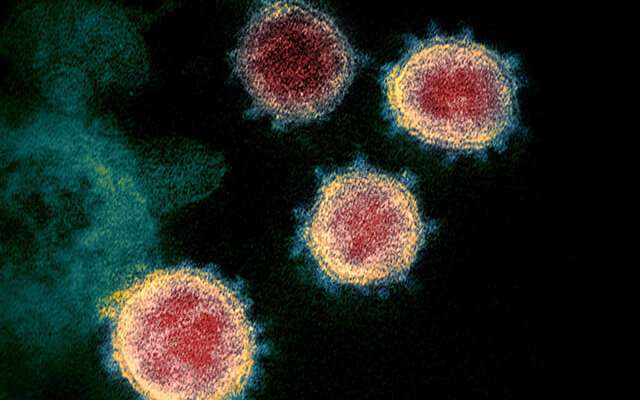

| Posted: 12 Jun 2020 07:24 AM PDT  In a Perspective piece published in the journal Science, a small international team of researchers is suggesting that the oral polio vaccine be tested to see if it might protect people from infection by the SARS-CoV-2 virus. In their paper, Konstantin Chumakov, Christine Benn, Peter Aaby, Shyamasundaran Kottili and Robert Gallo suggest the vaccine has been found to provide some protection against other viral infections, and point out that it has been proven to be safe over many years. Polio vaccines are, of course, vaccines that are used to prevent poliomyelitis infections. They have been in use since the 1950s. Polio vaccines come in two varieties: inactivated (administered by injection) and weakened (administered orally). Together, the two vaccines have nearly eradicated polio. They have also been found to confer some degree of immunity against other types of infections, both bacterial and viral. In their paper, the researchers argue for testing to see if the oral (weakened) vaccine might prove effective in preventing COVID-19 infections. They confer some degree of immunity against other infections because they activate an innate immune response, known as the first line of defense response. In contrast, immunity is conferred against certain viruses when a person is infected with it specifically, because the body produces antibodies specifically geared towards fighting it. The authors of the Perspective piece suggest that activating the first line of defense via the oral vaccine may be all some people need to ward off COVID-19 infections. They note also that recent research has shown that the SARS-CoV-2 virus can suppress the innate immune response in patients with more serious symptoms. The authors suggest the oral vaccine as opposed to the injectable kind be tested because the injectable vaccine does not activate an innate immune response, and because it is already licensed for use in the United States, the country that has thus far been hit hardest by the pandemic. They acknowledge that there is some small risk of using the oral vaccine, as it has been found to generate circulating vaccine-derived polioviruses, a type of polio that is vaccine derived in a very small number of people, mostly children with compromised or underdeveloped immune systems. But they suggest that if it does prove to ward off coronavirus infections, the good that could come from its use would far outweigh the bad. Explore further More information: Konstantin Chumakov et al. Can existing live vaccines prevent COVID-19?, Science (2020). DOI: 10.1126/science.abc4262 © 2020 Science X Network Citation: Researchers suggest oral polio vaccine be tested to see if it might help against SARS-CoV-2 (2020, June 12) retrieved 30 June 2020 from https://medicalxpress.com/news/2020-06-oral-polio-vaccine-sars-cov-.html This document is subject to copyright. Apart from any fair dealing for the purpose of private study or research, no part may be reproduced without the written permission. The content is provided for information purposes only. |

| You are subscribed to email updates from "poliomyelitis symptoms" - Google News. To stop receiving these emails, you may unsubscribe now. | Email delivery powered by Google |

| Google, 1600 Amphitheatre Parkway, Mountain View, CA 94043, United States | |

Comments

Post a Comment