An epidemic’s legacy can be unpredictable - Daily Press

An epidemic’s legacy can be unpredictable - Daily Press |

- An epidemic’s legacy can be unpredictable - Daily Press

- The arrival of the first polio vaccine in St. Louis in 1955 was greeted with relief - STLtoday.com

- Keep Off This Street: The Epidemics of Polio and COVID19 - WMNF - WMNF

| An epidemic’s legacy can be unpredictable - Daily Press Posted: 02 Apr 2020 12:00 AM PDT  Throughout the summertime of the late 1940s and early 1950s parents were frightened to allow their children to play outside because of poliomyelitis outbreaks. This widespread virulent disease produced anxiety, death and life-altering disabilities to vulnerable juveniles in every state. At its zenith in 1952, more than 3,000 died and 21,000 were left with mild to significant paralysis. |

| The arrival of the first polio vaccine in St. Louis in 1955 was greeted with relief - STLtoday.com Posted: 21 Apr 2020 12:00 AM PDT   Lesley Rabon, 8, a student at Jackson Park Elementary School in University City, receives one of the first free polio vaccinations in St. Louis on April 21, 1955. Giving the shot is Dr. Guy Magness, while school nurse Peggy Vaugh assists. The National Foundation for Infantile Paralysis had bought 7.5 million doses to distribute to the nation's schools. The first wave of inoculations was for first- and second-graders. Post-Dispatch file photo ST. LOUIS • Two leaders of a mothers' campaign met the train downtown on April 21, 1955. An express worker handed them the first box of a miracle shipment. "This is a wonderful victory," said Loretto Gunn, co-chair of the Mothers March on Polio. "The mothers of St. Louis have been looking forward to this for years." Mothers, and everyone else, awaited the first cartons of Dr. Jonas Salk's electric discovery, a vaccine to prevent the dreaded crippler and killer known as poliomyelitis. The baggage car from Indianapolis brought free cartons of Salk vaccine for schoolchildren in St. Louis and St. Louis County. Three days earlier, a truck from Springfield, Ill., delivered a shipment to Belleville, where the first shots were given at St. Henry's Catholic School. On that day, the St. Louis group didn't know when its vaccine would arrive. Such was the confusion in the harried effort to vaccinate the nation's first- and second-graders as quickly as possible. Polio is a viral disease transmitted by human contact. (It also was called infantile paralysis, even though it afflicted adolescents and adults.) Most people had no serious symptoms, but a few died or suffered permanent physical disabilities. Epidemics periodically swept the country. President Franklin D. Roosevelt lost the use of his legs as a young man due to the disease. Polio put children in bulky braces and iron lungs, the barrel-shaped machines that kept them breathing with air pressure to move their paralyzed diaphragms. The list of symptoms was distressingly unhelpful — fever, tummy ache, aching muscles. If a child complained of a sore leg, parents didn't sleep that night. In our age of medical wonders, it may be hard to appreciate the depth of the relief that greeted Salk's vaccine. Doctors in Europe had formed a diagnosis in the 19th century, but people could do little but fret. Shriners Hospital for Crippled Children opened at 700 South Euclid Avenue in 1924 to serve polio patients. For decades, its 100 beds usually were filled. Before the vaccine, headlines announced new cases, deaths and the effort to raise money for research. Summer was considered the "polio season," but that was a function of humans mingling, not temperatures. As clusters of cases erupted, officials closed schools and swimming pools. An epidemic in 1949 killed 64 people in the St. Louis area. In August 1951, four of the five children of Mr. and Mrs. Joseph Schwane of Marthasville contracted polio. Two of them died within three weeks. Salk led a research team in Pittsburgh that developed the vaccine. As final tests were conducted, drug manufacturers stockpiled serum. When approval was announced April 12, 1955, the rush was on. The National Foundation for Infantile Paralysis (March of Dimes) bought enough vaccine for the free shots nationwide. Newspapers ran long lists of vaccination times at schools, and more than 50,000 eligible St. Louis-area children lined up for shots. It took several years of vaccinating children and adults, but the number of cases eventually fell significantly. St. Louis reported its last naturally occurring case in 1963. Salk died in 1995 at age 80. Iron lung patient Verne Muskopf, a nurse at St. Anthony's Hospital, South Grand Boulevard and Chippewa Street, helps iron-lung patient Louis Abercrombie smoke a cigarette in November 1949. Abercrombie was a polio patient and had been in an iron lung for almost three years. Hospital policies on smoking were different then. Post-Dispatch file photo Iron lung patient A polio patient gets treatment in an iron lung at St. Louis Isolation Hospital, 5600 Arsenal Street, in January 1942. Iron lungs used alternating air pressure to expand and contract the patient's diaphragm, allowing her to breathe. Polio could paralyze the diaphragm muscles, sometimes permanently. Standing with a nurse are (left) Francis Dunford, St. Louis chairman of the National Foundation for Infantile Paralysis; and Mrs. Arthur Krueger, district president of the Missouri Federation of Women's Clubs, which donated the device. Post-Dispatch file photo Recuperating from polio Eleanor Hayes, a physio-therapist at St. Louis County Hospital's polio unit, helps a four-year-old patient to learn how to walk again in December 1947 after he was afflicted by the viral disease. The unit was opened after 581 adults and children in the St. Louis area came down with polio during an epidemic in 1946. Photo by Jack Gould of the Post-Dispatch March of Dimes campaign Three young polio patients meet with leaders of the St. Louis March of Dimes for a KSD-TV special program in December 1951 to raise money for research. They are (from left) Sandra Paxton, Kay Sanders and David Robinson. Standing are (left) Joseph Kelly Jr., chairman of the city-county chapter of the National Foundation for Infantile Paralysis, and former St. Louis mayor Aloys Kaufmann, vice-chairman of the annual drive. Post-Dispatch file photo Campaign for polio vaccine One of the floats in a parade on Jan. 28, 1954, for the Mothers March on Polio. The statue of St. Louis holds a test tube to symbolize research to cure or prevent the disease. On the float are polio patients (left) Karen Coffey of Ferguson and David A. Robinson of 1318 North Market Street. Post-Dispatch file photo Living with effects of polio Arlene Harwell, a polio patient, works the switchboard at Laclede Insurance Co., 220 North Fourth Street, in January 1954. She was featured in an article on how polio patients adapt their lives. Post-Dispatch file photo Dr. Jonas Salk Dr. Jonas Salk, who led the research team that developed the polio vaccine, in his laboratory at the University of Pittsburgh in April 1955, shortly before approval for distribution. United Press International photo Dr. Jonas Salk explains vaccine Dr. Jonas Salk (left at podium) explains development of the vaccine during a gathering on April 13, 1955, at the University of Michigan. With him are (center) Dr. Thomas Francis Jr., who led statistical research; and Basil O'Connor, president of the National Foundation for Infantile Paralysis, which raised money for the research. Associated Press photo Vaccine arrives in St. Louis St. Louis-area leaders of the campaign to combat polio greet a passenger train at Union Station on April 21, 1955, that brought the first shipments of free vaccine for first- and second-graders. Station employee Walter Goyda hands the first box to Bernard Dickmann, chairman of the St. Louis March of Dimes committee; and (left) Jessica Barco and Loretto Gunn, co-chairwomen of the local Mothers March on Polio. Behind the box is Dr. J. Earl Smith, city health commissioner. Dickmann also was St. Louis postmaster and a former mayor. Photo by William Dyviniak of the Post-Dispatch Getting a polio shot Lesley Rabon, 8, a student at Jackson Park Elementary School in University City, receives one of the first free polio vaccinations in St. Louis on April 21, 1955. Giving the shot is Dr. Guy Magness, while school nurse Peggy Vaugh assists. The National Foundation for Infantile Paralysis had bought 7.5 million doses to distribute to the nation's schools. The first wave of inoculations was for first- and second-graders. Post-Dispatch file photo Getting polio shots Students from St. Mary's School wait for a bus after they received their polio shots at Harris School in Madison on April 18, 1955. They were among the first 12,000 students in the Metro East to receive the shots through the free national program. Post-Dispatch file photo Polio vaccinations Gleason Knox, a student at Harris School in Madison, grimaces as Dr. Irving Wiesman gives him one of the first vaccination shots in the St. Louis area on April 18, 1955. The Metro East received a partial shipment of the vaccine three days before St. Louis did. The vaccine was made available to first- and second-graders nationwide during a program financed by the National Foundation for Infantile Paralysis shortly after the vaccine was approved for use. Assisting the doctor is Marjorie Cross, a member of the school mothers' club. Post-Dispatch file photo Polio vaccine drive Approval of the Salk vaccine in 1955 was a watershed event, but polio cases continued during the national effort to inoculate everyone. In January 1959, leaders of the March of Dimes fundraising drive gather outside St. Anthony's Hospital, South Grand Boulevard and Chippewa Street, to promote the annual drive. The children are patients in the hospital's polio unit. With them are (left) Loretto Gunn, co-chairwoman of the St. Louis March of Dimes; and (center, in light-colored hat) a former St. Louis mayor who was chairman of the county campaign; and Jessica Barco (second from right) co-chair with Gunn. Post-Dispatch file photo Boy gets oral polio vaccine Keith Sisson, 2, takes an oral version of polio vaccine in July 8, 1970, with help from Sister Christine of DePaul Hospital, 2415 North Kingshighway. He was among 700 children who received the vaccine that day. Photo by Jim Rackwitz of the Post-Dispatch HIDE VERTICAL GALLERY ASSET TITLES1955: Polio Shots Patsy Murr, first grader at Fulton School in Lancaster, Penn., gets her Salk shot from Dr. Norman E. Snyder as she is held by Mrs. Walter Sourweine, April 25, 1955. Others view the proceedings with mixed emotions. (AP Photo) 1938: March Of Dimes In 1938, the March of Dimes campaign to fight polio was established by President Franklin D. Roosevelt, who himself had been afflicted with the crippling disease. 1954: Salk Vaccine In 1954, the first mass inoculation of schoolchildren against polio using the Salk vaccine began in Pittsburgh as some 5,000 students were vaccinated. 1950: March Of Dimes Five members of the Schofield family of Newark, N.J., all hospitalized in the 1950 polio epidemic but now recovered, turn over their March of Dimes collection boxes to Basil O'Connor, right, in New York, Jan. 24, 1955. The youngsters, still receiving follow-up treatment, conducted a family competition for funds for the drive. The Schofield case represents the greatest incidence of polio among brothers and sisters of one family reported to the National Foundation for Infantile Paralysis in 1950. From left to right are: George, 4; Andrew, Jr., 14, back; David, 8; Robert, 11, and Mary Jo, 9. O'Connor is president of the foundation. (AP Photo/Jacob Harris) 1962: Iron Lung Joanne Hawrylchak, 9, of Richfield Springs, smiles from her iron lung in Albany, N.Y., as Lt. Joy Lane, Air Force nurse, prepares her for a flight to New York City aboard a Military Air Transport Service plane, Jan 17, 1962. Joanne, a polio victim, will receive treatment at a rehabilitation center there. (AP Photo) Tim O'Neil is a reporter at the St. Louis Post-Dispatch. Contact him at 314-340-8132 or toneil@post-dispatch.com Get local news delivered to your inbox! |

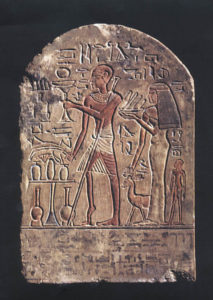

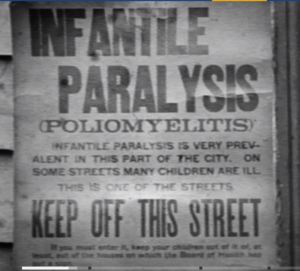

| Keep Off This Street: The Epidemics of Polio and COVID19 - WMNF - WMNF Posted: 27 Apr 2020 04:51 PM PDT  Share this: The epidemics of polio and COVID19Empty beaches, hollow pools, abandoned and quiet streets. Bans on gatherings. Fear layering daily activities with hesitation, and loss. While the Spanish Flu of 1918 is evoked by the onset of the latest coronavirus, another epidemic lingers in memory. Polio ravaged children and adults in the first half of the 20th century, appearing in the summer after school let out. The very places of pleasure – movie houses, public pools, the warm white sand of the Gulf, seemed ominous and dangerous. At its peak, polio affected 37 out of every 100,000 people. about 38,000 each year. What can we learn by looking at the similarities and differences of polio and COVID19? A little pandemic historyEpidemics transmit in different ways. Some require intimate contact, such as Ebola, or intimacy and/or intimate fomites (objects or material carrying the disease), such as HIV/AIDS. Many transmit through the air (through droplets or aerosol, or both), such as the Spanish Flu. There is no definitive proof yet that people can get COVID19 infections through only droplets or only oral spray. Health officials recommend protecting yourself in multiple ways. Today's unbalancing uncertainty about the virus and its transmission also happened with polio. It started in the late 19th century and blossomed fully by the mid-20th. Before that, there were several epidemics and pandemics in the 19th century – cholera, typhus, smallpox, yellow fever, and the plague. Poverty, overcrowding, and international trade, which brought diseases into the cities and ports, accelerated both the epidemics and the anger at the inability of the governments to curb the impact of them. The Western world shifted from primarily agrarian to more urban with the industrial revolution in the 18th and 19th centuries. Understanding about how diseases spread, and could be treated, challenged traditional medical practices. Quarantining entire populations during epidemics, and mistrust of the medical establishment resulted in protests and riots in Russia, Germany, and England. Protests? Looks like we have reached that stage in the pandemic playbook right now. There were worker strikes and riots during the Spanish Flu as well, against autocratic or ineffective governments. There weren't polio riots though.  Egyptian Stele depicting polio victim By Fixi, CC BY-SA 3.0 PolioPoliomyelitis and civilization developed together. An ancient Egyptian stele depicts a possible polio victim, dating from around 1400 BC. Polio didn't reach epidemic proportions though until the modern age. Infants might contract polio in its mildest form, and develop immunity, or get the immunity as they nursed from a mother who had it. But as sewer systems were cleaned up and public health measures were taken to battle other diseases, widespread immunity against polio declined. Immunity to the disease, then called Infantile Paralysis, no longer was transmitted through mothers' milk or developed early. Children, instead of infants, began to get polio, with more severe symptoms and greater risk of paralysis. DesperationThe entire planet reels from the COVID19 pandemic. Governments shut down most businesses and public areas. People are told to stay home, while scientists and medical teams try to figure out how it is transmitted; how long the virus can survive on surfaces; and whether immunity develops in those who have had it. The president suggests dangerous or ineffective treatments, and the internet picks those ideas up and a misinformation pandemic spreads as well – another similarity between polio and COVID19. There were some dangerous treatments for polio as well. Texas sprayed its towns with DDT.

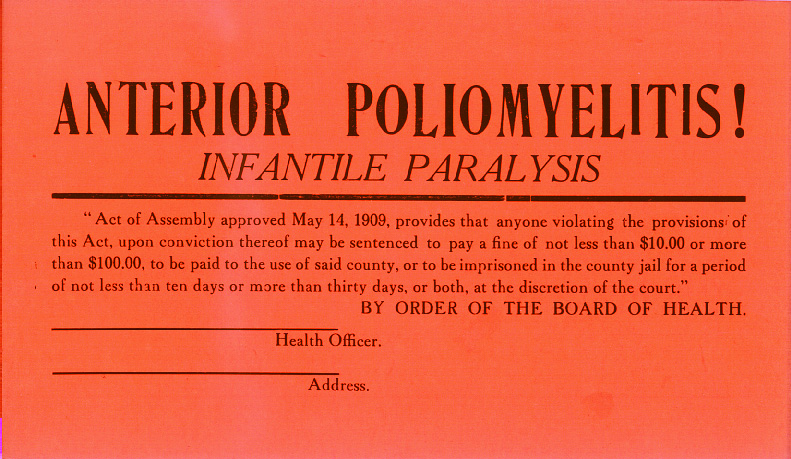

People believed that warm water could cure polio, yet also believed that it could be caught in pools, lakes, and other bodies of water. What was clear was that polio was a highly contagious disease. Quarantines, aka shelter at home and social distancing, were invoked when the disease would show up, usually in the summer.  Polio signs were put on afflicted houses. Katherine Meacham Conover remembers in 1930s Memphis, when she was a child, pools being closed. Doors were marked when there was a house with a polio victim. Later, a college friend and her three children developed polio. The kids were okay, but her friend was permanently afflicted. The government installed a pool in her back yard to help her rehabilitation, and she had a car that she could drive with just her hands. And yes, Memphis also sprayed DDT. Musician Gary Z, who contracted a mild case of polio when he was young, still remembers a visit to the hospital 66 years later. "I was quite fortunate as other kids in my hometown (PA) were not so lucky. In 1954 my mother took me to the local hospital to visit a classmate (first-grade) who had been stricken and was in an iron lung. The visit with him has always stuck in my mind. To this day I clearly remember talking to Michael as he lay there. He was somehow cheerful and happy we had come to visit. I never saw him again. Quite sad but a slice of Americana. Happy days followed as the Salk vaccine was developed a year or so later."  Polio vaccine history, from FB post Hope emergesBut here is a better memory. In 1953, a small scale polio vaccine trial happened at the elementary schools near Carnegie Institute of Technology, now called Carnegie Mellon. Dr. Jonas Salk has a small team working on a vaccine, and needed 700 students for a trial. The Meachams were a faculty family at Carnegie, with Katherine's husband teaching math. Their eldest son Robert attended Squirrel Hill Elementary School near the campus. "Of course we wanted to be part of the trial," Mrs. Meacham Conover said. "Children were either given the real vaccine or a (placebo). They told us later that Robert had gotten the real thing." The success of that small trial led to a bigger one, and then an even bigger one, and in April 1955, the vaccine was pronounced safe and effective, and ready for wide distribution. Polio was largely erased from the United States over the following decade. Most Americans strongly support social distancing and other measures to prevent the spread of COVID19 (8 in 10, according to a recent poll by Politico/Morning Consult), though there are some well funded but small protests against the restrictions. Were people as amenable during the height of polio? Gary Z. thinks that the post-war mentality in the 1940s and 1950s contributed to a 'lax' mentality. From the top downThe national context of polio in the United States during the first part of the 20th century was largely shaped by President Franklin Roosevelt. He contracted what was thought to be polio in 1921, when he was 39, which both paralyzed him, and led to his strong activism. It also shocked the nation that a rich, connected, well known politician could get polio. Roosevelt started the Warm Springs Foundation in 1927, designed to help people with polio not only improve, but be independent and high functioning in a society that often shunned and limited them. Elected to the White House in a landslide in 1932, Roosevelt held Birthday Balls to raise money for polio research and to help provide treatment. In 1938 he transformed the Warm Springs Foundation into the National Foundation for Infantile Paralysis, later rebranded as the March of Dimes by popular comedian Eddie Cantor. The idea was that even during the Great Depression, everyone could afford to give a dime to fight polio. Millions of dollars were raised and grassroot fundraising was born.

Silver linings?It might be hard to believe that good can come out of the COVID19 pandemic right now. Tens of thousands of lives lost, and millions of lives changed. An economy that now tilted, can crash. Months of education, work, projects, and plans have slipped away. But earlier pandemics and epidemics led to positive change. Maybe this one will too. Cholera epidemics in mid-1800s London led to understanding how dirty and infected water infected people, leading to cleaner municipal water systems. In 1919, British soldiers massacred hundreds of unarmed Indians (theJallianwala Bagh Massacre) protesting the way the British were handling the Spanish Flu epidemic. It is estimated 12-13 million Indians died in four months. The massacre and British failures led to the Indian independence movement, headed by Mahatma Gandhi, eventually leading to that country's self rule. Less known is Polio's profound effect on modern life. Physical therapy and rehabilitation, disability rights and universal design/access for all in public spaces were all either profoundly changed or invented in response to polio. The Warm Springs Foundation rejected the idea that the effects of polio should keep people from working, having families, and living. They were early prototypes for accessibility. The March of Dimes changed non-profit marketing, especially by using celebrities, and grassroots fundraising. What amazing things might come out of the COVID19 pandemic? Voting by mail, human impact on the environment, the health care system, transportation, and many other things are up for discussion. There could be a silver lining to these terrible dark clouds. |

| You are subscribed to email updates from "poliomyelitis symptoms" - Google News. To stop receiving these emails, you may unsubscribe now. | Email delivery powered by Google |

| Google, 1600 Amphitheatre Parkway, Mountain View, CA 94043, United States | |

Comments

Post a Comment