1946 polio case quarantines farm family | Yarns of Yesteryear - Leader-Telegram

1946 polio case quarantines farm family | Yarns of Yesteryear - Leader-Telegram |

- 1946 polio case quarantines farm family | Yarns of Yesteryear - Leader-Telegram

- CDC Director Says 1 In 4 May Have No Coronavirus Symptoms : Shots - Health News - NPR

- Remember when: Polio epidemic of the 1950s - The Andalusia Star-News - Andalusia Star-News

| 1946 polio case quarantines farm family | Yarns of Yesteryear - Leader-Telegram Posted: 30 Mar 2020 03:00 AM PDT  The year was 1946. World War II had ended, but the state and national concern that year focused on a new enemy, poliomyelitis, better known as infantile paralysis, or polio. Our family lived on an 80-acre dairy farm in Manitowoc County, which did not have electricity or indoor plumbing. We relied on a windmill to pump our water or had to resort to pumping it by hand. We hand milked 15 cows twice a day. Needless to say, farming was a struggle then, and to make matters worse, my three-year-old sister, Dianne, suddenly became sick in June of that year with what our family doctor diagnosed as polio symptoms and advised that she be taken by ambulance to a hospital in Madison that was set up to handle polio patients. Our family of eight was immediately placed under quarantine. We were devastated. For one month none of us were allowed to milk our cows, but our concerned neighbors were quick to volunteer to milk our cows each day and to deliver safe drinking water for the family. The milk could not be sold for human consumption, so we either had to feed it to the hogs or dump the daily supply on the manure pile. No income that month. The outhouse had to be sanitized with a heavy sprinkling of lime. These were precautionary measures advised by the county health nurse as they did not know the cause of the virus. The county nurse did visit our family weekly to check our status. This episode took place during summer months, so it did not affect our schooling. As a 15-year-old, I was working at a local chick hatchery, and my boss's younger daughter had also contracted polio and ended up with a deformed leg and paralysis. My sister has fully recovered, has no evidence of the setback and the medical personnel never found a correlation between the polio affliction of my three-year-old sister and the chick hatchery girl. Fortunately the Salk vaccine was developed at a later date, and since that time polio has been kept under control in the United States, although there are sporadic outbreaks in remote places of Africa and the Middle East where medical personnel find it difficult to reach the stricken. Now, here we are 74 years later and suddenly our entire world is faced with a pandemic, a new virus better known as coronavirus. It has placed a tremendous strain on our medical handling of this sweeping attack as well as an economic setback of unmeasured proportions if the disease is not harnessed. I called my sister Dianne last weekend and we both agreed that we have lived through the era known as "The Greatest Generation" and may never experience again the good life that we had. Dad died of a heart attack at age 75, and our hardworking mom died of pancreatic cancer at age 85. All eight of us offspring, ages 66 to 89 are still living and are in reasonably good health. Sure, we lived through some rough times, but as our dad used to say, "We may not make much money farming but at least we eat good and overall we are in good health." Dad was a great provider by raising livestock and a large garden. Mom was an excellent cook and a caring mother. The names of two people come to mind that were stricken with polio but despite the handicap led fruitful lives. Many of us remember Jack Hackman, who was born and raised in Pittsville. He went on to become an executive officer of WDLB radio in Marshfield and a leader and worker of many foundations in Marshfield. The other person, Franklin Delano Roosevelt, stricken with polio that crippled both legs, was elected U.S. President in 1933 and held that office for 4 consecutive terms. Known for coining the term, "The only thing we have to fear is fear itself," he died at the age of 63 in the early stage of his 4th term in office. Although polio limited his mobility, he was still able to govern. Once again we are being asked to change our lifestyle and make adjustments to overcome or conquer this dreaded disease. Quarantines are now being established and updated medical advice is being sent out via radio, television or in print. It's a tipsy-topsy world we live in. It behooves us to follow medical recommendations, hoping that we can return to a life style that we have lived through or still seek. At the moment those visions seem bleak. My sister and I found one ray of humor in our discussion in that our family never experienced a shortage of toilet paper as we relied on Sears-Roebuck or Penney's catalogs. |

| CDC Director Says 1 In 4 May Have No Coronavirus Symptoms : Shots - Health News - NPR Posted: 31 Mar 2020 09:20 AM PDT  Dr. Robert Redfield, director of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, speaks at a House Committee on Oversight and Reform hearing about the coronavirus on March 11. Michael Brochstein/Echoes Wire/Barcroft Media via Getty Images hide caption  Dr. Robert Redfield, director of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, speaks at a House Committee on Oversight and Reform hearing about the coronavirus on March 11. Michael Brochstein/Echoes Wire/Barcroft Media via Getty ImagesWhen infectious pathogens have threatened the United States, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention has been front and center. During the H1N1 flu of 2009, the Ebola crisis in 2014 and the mosquito-borne outbreak of Zika in 2015, the CDC has led the federal response. Yet the nation's public health agency, with its distinguished history of successfully fighting scourges such as polio and smallpox, has been conspicuously absent in recent weeks as infections and deaths from the new coronavirus soared in the U.S. President Trump has been holding almost daily press conferences at the White House, but the primary health advisers at his side are not from the CDC. Dr. Anthony Fauci directs the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, which focuses on biomedical research, and Dr. Deborah Birx is the global AIDS coordinator for the State Department. The public has heard much less from the CDC director, Dr. Robert Redfield, and the agency, based in Atlanta, has not held a media briefing since March 9. On Monday, Redfield agreed to a phone interview with Sam Whitehead, the health reporter at WABE in Atlanta, where he also hosts a coronavirus podcast. This interview has been edited and condensed for length and clarity. Has the CDC learned anything new about the virus, such as how contagious it is or how it is transmitted, in recent weeks? Let's take transmission. ... This virus does have the ability to transmit far easier than flu. It's probably now about three times as infectious as flu. One of the [pieces of] information that we have pretty much confirmed now is that a significant number of individuals that are infected actually remain asymptomatic. That may be as many as 25%. That's important, because now you have individuals that may not have any symptoms that can contribute to transmission, and we have learned that in fact they do contribute to transmission. And finally, of those of us that get symptomatic, it appears that we're shedding significant virus in our oropharyngeal compartment, probably up to 48 hours before we show symptoms. This helps explain how rapidly this virus continues to spread across the country, because we have asymptomatic transmitters and we have individuals who are transmitting 48 hours before they become symptomatic. We know there is asymptomatic spread. ... Are you taking another look at the CDC's mask recommendations? We're always critically looking at new data and ... there is data from obviously Singapore, Hong Kong and China that looks at the issue and you can look at masks in two ways. ... Is the mask something that protects me or ... if I wear a mask, is it something that protects others, from me? Particularly with the new data, that there's significant asymptomatic transmission, this is being critically re-reviewed to see if there's potential additional value for individuals that are infected or individuals that may be asymptomatically infected. ... Obviously you can see the complexity of that, if you assume that 25% are asymptomatic, the only way you would do it — if you then sort of went into areas that were high transmission zones and had a significant [proportion of] individuals then wearing masks, assuming that they were infected. I can tell you that the data and this issue of whether it's going to contribute [to prevention] is being aggressively reviewed as we speak. Coronavirus models the Trump administration has been looking at suggest an initial surge in hospitalizations and deaths in April or May. But [after those surges] 95% of Americans will still have not been exposed to this virus at all. To protect those 95% of Americans, won't we need massive testing all over the country to control any renewed spread? Most respiratory viruses have a seasonality to them, and it's reasonable to hypothesize — we'll have to wait and see — but I think many of us believe as we're moving into the late spring, early summer season, you're going to see the transmission decrease, similar to what we see with flu as the virus then moves into the Southern Hemisphere. We will then have a period of time to continue to work on countermeasures. As you know, there's a number of states right now that have limited transmission, and so getting back into those states with the public health community for early case definition, isolation, contact tracing, I think this is what we're going to be doing very aggressively May, June, July — to try to use those standard public health techniques to limit the ability to have wide-scale community transmission as we get prepared, most likely, for another wave that we would anticipate in the late fall, early winter where there will still be a substantial portion of Americans that are susceptible. Hopefully, we'll aggressively reembrace some of the mitigation strategies that we have determined had impact, particularly social distancing. "This is a very powerful weapon" First, I'd like to thank all the Americans and all the people in our nation that have taken this to heart and really practice aggressive social distancing. Secondly, for those that are still on the sidelines, I'd like to tell them now's the time to really embrace this. This is not just a little recommendation on a piece of paper. This is a very powerful weapon. This virus cannot go from person to person that easily. It needs us to be close. It needs us to be within 6 feet. If we just distance ourselves, this virus can't sustain itself and it will go out. I'm reminded about the NBC [motion graphic] and it's now on my Twitter, lining up matches and then lighting the match, and they all light and then you just take out one match and the fire goes down. So this social distancing that we're pushing ... is a powerful weapon, and that will shut this outbreak down sooner than it otherwise would have been shut down. And as next season comes up, it's going to be important that we reembrace that social distancing. When will the CDC have some kind of public tracking system of every single test result in the country, whether that's done in a hospital or by a public or commercial lab? Knowing where these cases are prepares you to respond. I think we're really close. I mean, we get daily reports from all of the testings coming in. Obviously, FEMA is the data coordinating center, but I think really strong, integrated data is currently occurring down at the county level, where we're getting positive tests, and where we're seeing new clusters, and where we are responding. One of the critical areas is, of course, long-term-care facilities. We now have over 400 long-term-care facilities in this nation that have now outbreaks. We're constantly going into those care facilities trying to limit these outbreaks or obviously trying to prepare other assisted living centers. At the end of the day, most of us who get this infection will recover. The majority of people do — probably 98%, almost 98.5%, 99% recover. The challenge is the older, the vulnerable, the elderly, those with significant medical conditions where this virus has shown a propensity to have a significant mortality. Once we know what the outbreak truly looks like, local public health agencies will need to respond. What is the CDC's plan to help with those efforts long-term? One thing that I think this coronavirus outbreak has really illustrated, something I've said since I came into this position, is we should be overinvesting in public health, overpreparing not underpreparing. Can you commit to actual money or personnel to do that work? What, practically, does that help from the CDC look like? The CDC provides between 50% and 70% of the public health funding for all state, local, territorial and tribal health departments. Clearly with the first supplemental [coronavirus funding from Congress] that came, CDC got additional funding ... [we sent] close to $565 million out to the state and local health departments to begin to let them expand their local capacity. With the third supplemental, CDC is getting an additional, I think, close to $4.4 billion, most of which is going to go out to help. But it doesn't help if we can't create these jobs in a way that individuals want to come and enter the public health workforce. So we're going to continue to try to increase, encourage and facilitate the local, state and territorial health departments to have the resources to hire these individuals as we try to motivate many in the American public to say that this is a great vocation to be part of it. [March 30] is actually National Doctors Day, but rather than just thank doctors today, I want to thank all the health care workers and all the public health workers, all the first responders. We have areas in Georgia where we still don't have confirmed cases, but we can't assume that there aren't cases there. Some of those same counties don't have robust health care systems. So how does the CDC convince people in counties like that, or officials in counties like that, to take this outbreak seriously? We are continuing to try to provide additional resources and guidance. We will be expanding surveillance throughout the United States so that we'll have a better eye on where this virus is. We'll be working with the state and local health departments to do that. As we get to a time where we're able to begin to start to reopen some of the economy, based on data showing that this outbreak is now at a point where that balance can be met ... we have to make sure we don't then have new, huge community clusters [in] these areas that have had very limited transmission. So we do have the resources to go in there and make that early diagnosis of those original cases through the isolation, contact tracing. "This virus is going to be with us" I don't think anybody would disagree that for decades, collectively, our nation's underinvested in public health. Now, I think people understand that that can really have significant consequences, and now is the time for us to overinvest overprepare in public health. This virus is going to be with us. I'm hopeful that we'll get through this first wave and, and have some time to prepare for the second wave. I'm hopeful that the private sector in its ingenuity and working with the government, NIH, will develop a vaccine that ultimately will change the impact of this virus. But for the next 24 months, you know, we're all in this together, and the most important thing that we can do is twofold: the American public fully embracing the social distancing that we requested to protect the vulnerable; and secondly, to operationalize the bread and butter of public health — you know, early case identification, isolation, contact tracing — so that this outbreak does not get the upper hand, as it has, unfortunately, in New York City, in northern New Jersey, and now New Orleans. We've seen here in Georgia municipalities and counties taking a piecemeal approach to issuing stay-at-home orders or other kinds of prevention measures. It seems naive to think that people don't cross city or county lines or even state lines. What can the CDC do to encourage a more unified response? I think the big thing is that in order to operationalize this, you really do need not only the buy-in of the American public, but you do need the buy-in and guidance of the civil leaders. We can put out strong, sound public health advice to try to motivate people to embrace these. I think early on, maybe the younger generation may not have embraced them as greatly as the older generation. My sense now is there's a greater embracement by really all segments of society. ... Yes, if you're young and healthy, you're likely going to do fine if you get this virus, but we're trying to protect the vulnerable. So I asked people to see the face of their parent or grandparent or their neighbor, or co-worker with diabetes or HIV, or kid trying to enjoy life [while] confronting cancer at a young age. We're doing it for them. ... It's a powerful weapon, and from what I'm seeing is the American public is responding. People want to be part of the fight. Is it possible to isolate vulnerable populations while allowing other people to let up [on the social distancing]? Is that something that we can actually do, let people have normal lives while still protecting the most vulnerable among us? I think there could be an evolution, and we're going to say that it's premature right now. We want the whole nation to stay all in, as the president announced the other day, to the end of April. We're going to be looking at data. It is important that one size doesn't fit all, and there are parts of our country that will — when they have the data to know exactly how much virus is in their community — they may be able to make local decisions that begin to allow parts of the economy to open up. And there'll be other jurisdictions that the data will say there's just too much extensive, widespread community transmission for us to do that. Now, I think you're going to see that analysis and that data be used to find that balance over the next four, six, eight weeks as our nation does come back to work. The last thing I wanted to say, just to be very clear, I have total confidence that we will get through this. I have total confidence that we'll bring this virus down, but the tool that we're going to do that is this request — for all Americans to really embrace the social distancing that we've requested. |

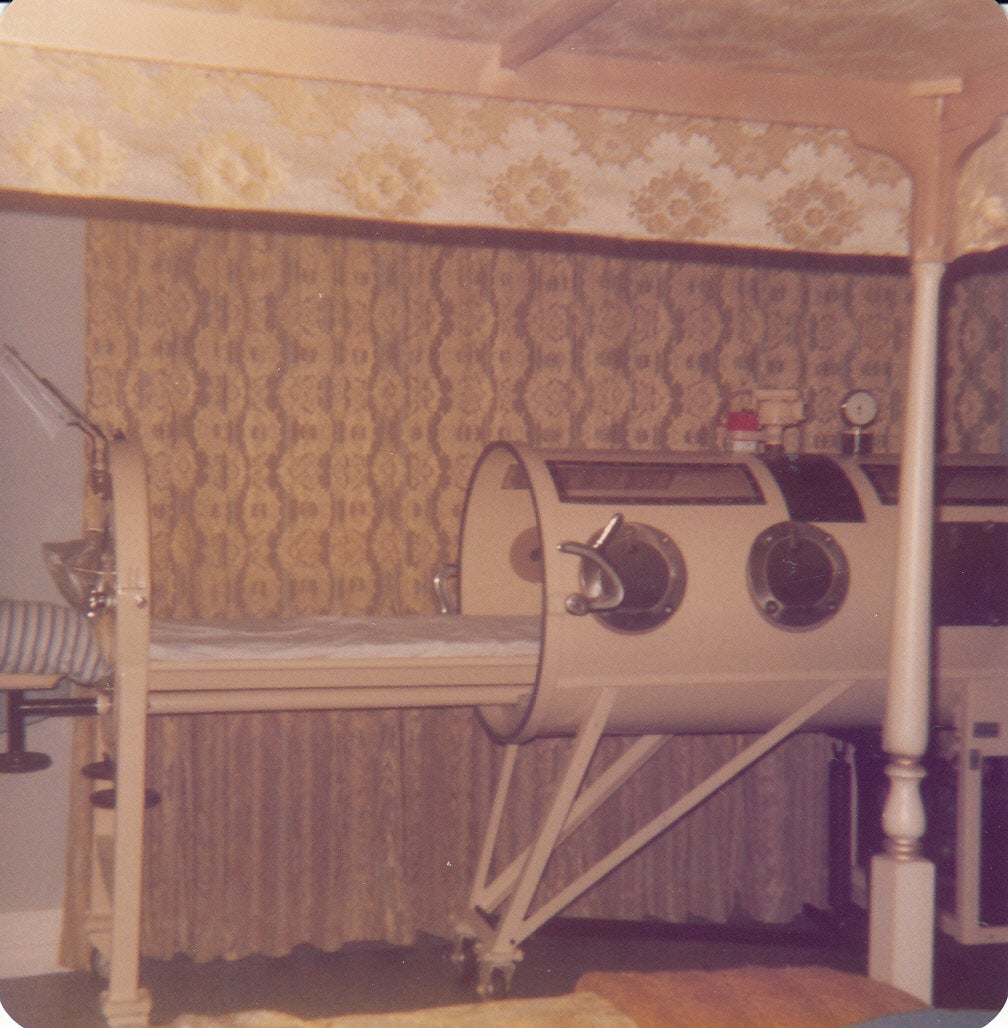

| Remember when: Polio epidemic of the 1950s - The Andalusia Star-News - Andalusia Star-News Posted: 28 Mar 2020 03:00 AM PDT  The history of polio infections extends into pre-history. The disease has been traced back to almost 6000 years. The first major outbreak of polio occurred in the U. S. in 1916. Also known as poliomyelitis, polio caused widespread panic beginning in the late 1940s. In 1952, the polio epidemic was the worst outbreak in the nation's history at the time. 3,145 died and 21,269 were left with disabling paralysis. Outbreaks in the United States increased in frequency crippling an average of more than 35,000 people for several years. Parents were frightened to let their children go outside especially in the summer when the virus seemed to peak. Polio was once one of the most feared diseases in the U. S. in the early 1950s. It focused on public awareness of the need for a vaccine. Following the introduction of vaccines, the Salk vaccine, Inactivated Polio Virus (IPV) intramuscular injections, was made available in 1957 and a few years later, the Sabin Oral Polio Vaccine (OPV) was developed resulting in a decline of the number of cases. The number of polio cases fell rapidly to less than 100 in the 1960s and fewer than 10 in the 1970s. Although polio has been eliminated from most of the world, the disease still exists in a few countries in Asia and Africa. Even if you were previously vaccinated, physicians warn that a one-time booster may be needed before you travel anywhere that could put you at risk. Polio is an infectious disease caused by viruses that attack the nervous system. The viruses are only spread human to human by direct and indirect contact. Symptoms and signs of polio vary from no symptoms to limb deformities, paralysis, difficulty breathing, inability to swallow foods, and death. According to the CDC (Center of Disease Control), it is possible to prevent polio by vaccinations, and it may be possible to eradicate polio since great strides have been made. According to the WHO (World Health Organization), 1 in 200 polio infections will result in permanent paralysis. Cases of polio peeked in the U. S. in 1952 with 57,623 reported cases. Since the Polio Vaccination Assistance Act, the U. S. has been "polio free" since 1979. In 1921 Franklin Delano Roosevelt became permanently paralyzed from the waist down (whether from polio or Guillain-Barre' syndrome). Roosevelt who had planned a life in politics refused to accept the limitations of his disease, and he became the 32nd president of the United States from 1933 to 1945. In 1938, FDR founded the National Foundation for Infantile Paralysis now known as the March of Dimes who sought small donations from millions of individuals. Growing up in the 1950s, here is what I remember about that polio scare when I was a child. In the summertime, the children in my family and my friends in the neighborhood had to take about an hour nap. Because there was no air conditioning in the early 1950s, windows were open, and we could only hope for a breeze! Later on when we went swimming or got soaking wet under the water sprinkler, it was necessary and important that we dry off quickly because of the polio epidemic and the danger especially to children. My mother and many of her friends with children joined the March of Dimes as volunteers and would go around the neighborhoods and businesses asking for small donations. There would usually be a chairman. Those "dimes" were attached to a cardboard type card that I can visualize today exactly what it looked like. When a number of cards were filled, they were forwarded to the March of Dimes headquarters. There was even a drive at school for each child to bring a dime. Civic clubs would participate. The effort was widespread across America. The next thing I vividly remember about polio was that polio shots were administered at school. I must have been a difficult student since my mother was called to come to school to hold me down! I ended up pulling her maternity top off. That must have been about 1955 since my sister Julie was born that year. Those shots were big, and the liquid in the injection looked like thick non-dairy whipped topping! There was not just one injection. There were two that were given to school children a few months apart. Lordy! Then into the 1970s, the local Coterie Club of young ladies used to send club members to the Scherf Memorial Building to volunteer at the Crippled Childrens' Clinic in the downstairs area. I recall that a doctor would travel from Pensacola to work at the clinic several times a month. There must have been enough children affected in the surrounding counties to hold a regular clinic in Andalusia. My good friend Dan Shehan, former English teacher for many years at the Andalusia High School, suffered from an attack of polio as a child. I asked him this week to send me his story. I will share a portion with you readers. "I had just finished the 5th grade at Parker Elementary School in Panama City, Florida. I was 10 years old and had been spending the summer with my maternal grandmother, Lilly D. Everage, on East Watson Street in Andalusia, the town of my birth. Several of her grown children lived nearby. One owned a grocery store on Stanley Avenue a block away. I would walk to the store in the mornings and get the food she planned to cook that day. If it were peas and butterbeans, I would help shell them. In the afternoons, I would walk to one of the theaters, pay 25 cents, and sit through the showing several times." "One morning in August 1953, I awoke with a stiff neck and terrific headache. As the day progressed, I began to feel very weak. The next day, I could hardly get out of bed or stand up without help and was admitted to Covington Memorial Hospital. My parents, Comer and Helon Everage Shehan, were called, and they drove up from Panama City. Dr. Parker didn't know what I had at the time. By that evening, I could not even move, and my breathing had become very shallow. My parents decided to place me in the back seat of the car and drive me to a Pensacola hospital where a relative had arranged for a doctor to meet us at the emergency room." "I was placed on an examining table and told to be very still for a spinal tap. After the procedure, the doctor and the nurse left the room and I was alone since my parents weren't even allowed in the room. While lying there wondering what was the matter, I heard a scream from another room. I was put on a stretcher a little later, placed in an ambulance, and driven to another building in the dark of night. I was very thirsty and semi-conscious, but the nurse would only put a drop of water on my tongue all along. I had not seen my parents since arriving at the emergency room. I thought whatever was wrong with me must be so bad that I was being put to death!" "When I finally awoke the next morning, I found myself enclosed in a tank-like contraption with my head sticking out one end. I soon learned that is was called an iron lung. I was feeling much better and had no trouble breathing although I was unable to move my arms and legs. As I shifted my eyes to the left, I saw rain through one of the high windows. To the right, I saw my parents looking through a window at me. I wondered what was going on." "Unknown to me at the time is what had transpired during the night. After the spinal tap, the doctor met with my parents and relatives and gave them the news that I had Bulbar polio and would be dead within 24 hours. Mother is the one that had screamed. She would not accept the prognosis. She phoned her brother-in-law, Dr. Robert Earl Vickery, who was a student at the University of Alabama Medical School in Birmingham. He and one of his professors flew down to Pensacola to the Escambia County Hospital during the night. They asked if there was an iron lung in the hospital. The reply was yes, but no one knew how to use it! My uncle and his teacher had put me in the iron lung thus saving my life!" This story gets more intriguing and will be continued in next week's Remember When column. Thank you Dan Shehan, native Andalusian now residing in Savannah, Georgia.

Sue Bass Wilson, AHS Class of 1965, is a local real estate broker and long-time member of the Covington Historical Society. She can be reached at suebwilson47@gmail.com.

|

| You are subscribed to email updates from "poliomyelitis symptoms" - Google News. To stop receiving these emails, you may unsubscribe now. | Email delivery powered by Google |

| Google, 1600 Amphitheatre Parkway, Mountain View, CA 94043, United States | |

Comments

Post a Comment